From Songdo, South Korea to Lavasa, India via Egypt’s unnamed new capital, everywhere you look it seems someone’s building a brand-new city. How hard could it be?

Building a real city from scratch isn’t like playing Minecraft, Civilization or SimCity. Well, it is a little. But problems arise in reality that don’t come up in cyberspace, including vainglorious dictators, pompous architects, bureaucratic impedimenta and the fact that much of the best land is already inhabited by those intractable objects: pesky humans.

Nevertheless, after studying several urban planning projects around the world, we’ve mastered the step-by-step process of how to build your very own real city.

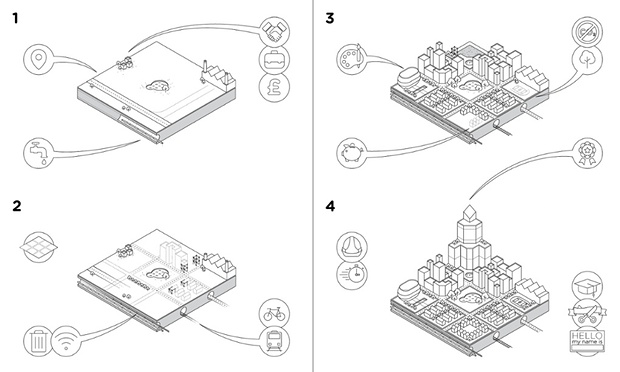

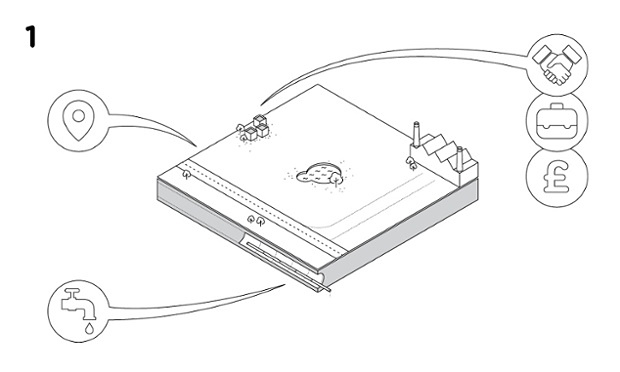

Step 1: Choose a location

Before you begin, you need a spot. Deserts, undeveloped jungles and uninhabited islands are popular: you don’t want to sink your budget into detoxifying brownfield sites, bulldozing slums or fighting legal battles over ancestral land rights. Plus, very few camels attend planning meetings, still less are they capable of forming coherent objections to your masterplan for a desert metropolis.

From our partners:

Tajikistan’s president, Emomali Rahmon, recently laid the foundation stone for Saihoon, a new city for 250,000 people on a 14,000-hectare (34,580-acre) desert site. When complete, it will have 19 residential districts, 50 schools, 40 sports centres, shopping centres and bazaars – and, my favourite design feature, 7,000 hectares (17,290 acres) of orchards blooming in the former desert. Egypt’s new capital, too, is going to be built on sand – to the east of Cairo, its functionally inadequate predecessor. Meanwhile, President Teodoro Obiang is currently overseeing the creation of Oyala as his new capital deep in the jungle of Equatorial Guinea, remote from the seaborne assaults that have menaced the dictator and his government in the existing capital. Crystal Island was to be built on a river island near Moscow.

If you don’t have a desert or uninhabited island to hand, build one. Songdo, the new city near Seoul in South Korea, is built on land reclaimed from the Yellow Sea. In the early 1960s, Buckminster Fuller dreamed up a giant floating pyramid in Tokyo Bay which would have housed 1 million people – in part as a response to the problem of acquiring building land in Japan. Perhaps sadly, it never got built.

Step 2: Ensure a reliable water supply

This may sound elementary, but consider what happened to the city of Fatehpur Sikri. The Mughal emperor Akbar commenced the construction of this walled city in 1569, to serve as the Mughal capital. Over the next 15 years, he and his lackeys built royal palaces, harems, courts, mosques and private quarters, all from locally available red sandstone. Shortly after completion, however, Akbar abandoned Fatehpur … in part because of inadequate water supplies.

Today, Rawabi – the first Israeli city built for Palestinians – has a similar problem. Work started in 2011 and, when complete, it will have homes for 40,000 residents, as well as cinemas, shopping malls, schools, landscaped walkways, office blocks, a conference centre, restaurants and cafes. But, until as recently as this spring, apartments stood empty because negotiations failed with Israeli authorities over connecting the city to the country’s water grid.

Step 3: Ensure a reliable money supply

Again this may sound elementary, but you don’t want to run out of liquidity halfway through building the high-speed train link to the financial quarter. There are various options available to you when it comes to securing the cash. Rawabi, denounced by some Palestinians for normalising Israeli occupation and by some Israelis for the possibility of providing a base for terrorists, has drawn a third of its $1bn (£640m) investment from the private Palestinian conglomerate Massar International, and the rest from Qatar.

Oyala has been described as “a multibillion-dollar plaything for Africa’s longest-serving dictator” and is funded chiefly by oil, timber and gas revenues. Equatorial Guinea is the third largest sub-Saharan oil producer, and much of that money is being lavished on the new capital, which will have a championship golf course, the Library of Central Africa (which looks like a spaceship docked in a jungle clearing), a luxury hotel and a presidential villa. Meanwhile, according to the International Business Times, “the people are starving”.

In Egypt, the nameless 700 sq km city that is set to replace Cairo as the country’s capital will be partly funded by Emirati businessman Mostafa Madbouly, who recently unveiled the £30bn project’s plans. He told Guardian Cities that he already has the money to build at least 100 sq km of the new capital, including a new parliament. But he needs more: which is why he invited kings, presidents, 30 visiting emirs and hundreds of would-be investors to the March launch at Sharm el-Sheikh.

Step 4: Think about jobs

If your city is to be economically sustainable, it needs jobs. Herbert Girardet, author of Creating Sustainable Cities, argues that Egypt’s planned new capital has a better chance of success than other purpose-built Egyptian cities, mainly because the vast government will be relocated there. Indeed, many of the most famous planned cities were new capitals – Brasilia, Canberra, Abuja, Canberra, Ottawa, New Delhi – that, whatever their other shortcomings, benefited from the employment opportunities and economic uplift of being a national administrative hub.

The first three of 100 smart cities that prime minister Narendra Modi is planning in India will be built as part of the Delhi-Mumbai Industrial Corridor, which the government aims will be a “global manufacturing and trading hub”. At Lavasa in Maharashtra, they’re planning animation and film studios, software-development companies, biotech labs, and law and architectural firms, focusing the knowledge industries at the heart of the “new India”.

Step 5: Do not alienate locals

Don’t do what they did in Lavasa. The developers of the 12,500-acre site have been accused of intimidating indigenous farmers into selling their land at rock-bottom prices. They have also been accused of cutting down millions of trees. Human rights activists have reported that up to 5,000 original settlers have been forced to leave. In 2010, the Indian Environment and Forests ministry ordered that construction on Lavasa cease because the project violated environmental laws.

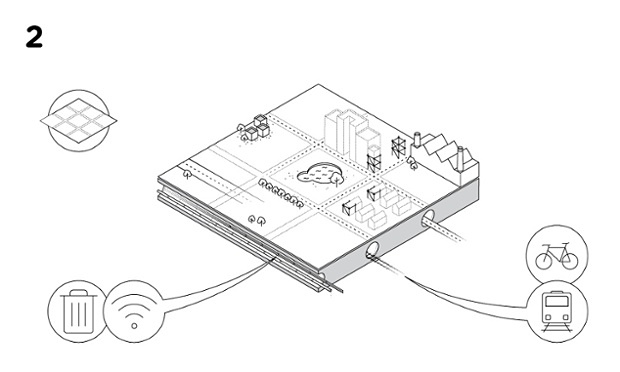

Step 6: Devise a masterplan

You don’t even need to set foot in the country where your plans will be realised. For example, Garsdale Design, which specialises in masterplans for war-ravaged cities in Iraq, is a family practice operating out of a converted barn in the Yorkshire Dales. Such 3D modelling applications as Esri CityEngine make it possible to devise city masterplans for homes, sewerage, water and electrical systems and integrated public transport, and then to amend these plans according to the needs on the ground. Increasingly, too, masterplans involve setting out Wi-Fi hotspots, fibre-optic grids and sensors (more on this below).

Step 7: Integrate transport

Narendra Modi’s 100 planned cities in India all involve integrated transport with bus rapid transport (or BRT, a sort of overground metro system), suburban trains and cycle networks. Smart transport might well mean digital parking meters that text you when a parking space opens up, or real-time transport displays that give data about traffic jams, availability of buses and train services. Helsinki – admittedly not a planned city, but a good model to follow – is going so far in the integrated transport direction as to say that private cars may soon be obsolete.

Step 8: Consider banning cars

Speaking of private cars being obsolete, Masdar City – designed by architects Fosters + Partners and being built by the Abu Dhabi Future Energy Company – has banned cars within its walls. Similarly, Dubai’s Ziggurat Pyramid, a metropolis planned in 2008 to house 1 million people, would have made cars redundant – its public transportation system, which would run horizontally and vertically, would be more efficient than private vehicles. (Sadly, since 2008 we’ve heard little of this putatively carbon neutral pyramid.)

Step 9: Make rubbish clever

Forget bin lorries, fetid dumpsters and the excrescence that is the wheelie bin. At Lusail City in Qatar, they’re planning a system of pneumatic tubes to transport rubbish to a central location for processing. At Songdo in South Korea, similarly, there are no rubbish trucks or bins in the street: all household waste is sucked into a vast underground network of tunnels and dispatched to waste-treatment centres where it is sorted and deodorised. Alternatively, information and communications technology can involve sensors that detect when waste disposal pickups are needed, or to measure energy consumption and emissions. Citizens may question whether they want ICT sensors checking their emissions. Ignore them. Whose city is this, anyway?

Step 10: Maximise connectivity

Broadband infrastructure that combines cable, optical fibre, and wireless networks is a basic requirement in such hi-tech cities as Songdo. What’s more, if you’re serious about creating a smart city, then you’ll need so much fibreoptic cabling that it’s not even funny – not enough just to ensure high-speed access to the internet, but also so that the sensors that are key to the development of intelligent solutions for the city can work properly. Otherwise you’ll have created not so much a smart city as a stupid one.

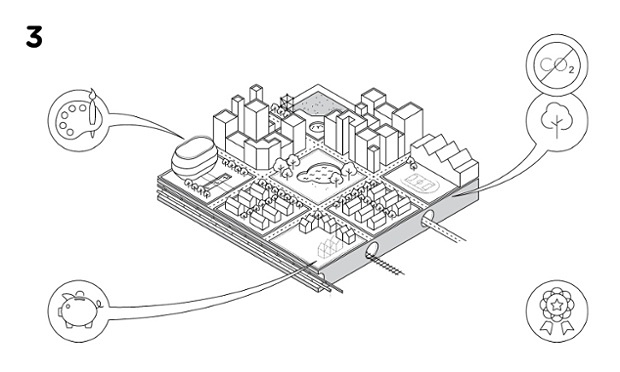

Step 11: Aspire to carbon neutrality

Destiny, the Florida city that developer Anthony Pugilese wanted to be a Silicon Valley of green technology, was, for a while, held up as a model: it aimed to reduce waste to close to zero and to meet its energy needs entirely through renewable sources including solar, wind, geothermal and the world’s largest hydrogen power plant. The city never got built: Florida authorities nixed the development, arguing that the ostensibly green and pleasant city amounted to urban sprawl.

Step 12: Start again, clown, you’ve forgotten parks

Look at your masterplan. Is it all sprawl and mall, dazzling plate glass, and more cloverleaf junctions than you can shake a stick at? Of course it is: most masterplans are. Humans can’t flourish in that environment, as good planners increasingly realise. Lavasa, for instance, is the first Indian city to be planned according to the principles of New Urbanism, which advocates walkable cities that commingle business and residential development, offer mixed-income housing, and preserve green space. Songdo has been planned around a central park, and designed so that every resident can walk to work in the business district – a big draw for attracting new residents. Sixty per cent of Great City, a high-density metropolis outside Chengdu in China, will consist of buffer areas of gardens and greenery that are at most 10 minutes’ walk from the city centre. And Egypt’s planned new capital will have a park double the size of New York’s Central Park.

Step 13: … and culture

Abu Dhabi has splashed its oil cash on a cultural city called Saadiyat Island, a few miles off the coast. It features a branch of the Louvre and before 2020 will also see a Guggenheim museum – designed, like the one in Bilbao, by Frank Gehry – and a Performing Arts Centre by Zaha Hadid. Just along the coast in Dubai, they’re playing catchup with D3 (short for Dubai Design District), in tacit recognition of the fact that shopping malls and gyms aren’t enough to make a city a decent place to live. Wags are already comparing the industrial Al Quoz area – which now has more than 30 galleries among its 1970s and 80s warehouses – to Shoreditch or Williamsburg. Just don’t expect any illegal raves or warehouse parties. Meanwhile, in the Congolese jungle, the Dutch artist Renzo Martens is trying something similar – to create an arts scene in one of the most impoverished parts of the world and thereby gentrify the jungle.

Step 14: Please, not another funny-shaped island

Does the world really need another state-of-the-art golf course? (At Lavasa they obviously think so: along with the medical campus, luxury hotels, boarding schools and sports academies, there is a Nick Faldo–designed golf course.) The worry about new cities built from scratch is that, as anthropologist Nick Simcik Arese of the Oxford Programme for the Future of Cities puts it, they offer a “secessionary envelope” for the rich – a form of class apartheid. He argues that new cities often fail to provide enough jobs for poorer residents or affordable transport to areas where they could find more work.

It’s an important point. Around the world, new cities often exclude all but the wealthiest. For instance, the least expensive apartments in Lavasa now sell for between $17,000 and $36,000 – well out of reach for most middle-class Indians. The developer says it has modified its plans to offer affordable rental apartments for young professionals. New cities are thus often confounded by the inverse relationship between maximising real-estate proceeds and making new cities livable. Or, to put it another way, if you want your new city to become something other than a ghost town or a large-scale gated community, it must be socially diverse.

What the world doesn’t need is any more unimaginatively shaped developments for those with more money than sense, such as the Palm Islands in Dubai. The entire point of the islands is that you can see them from space. On the ground, however, it means long spits of land that don’t connect to each other and leave you in a kind of endless residential street hellscape. Besides, what must our alien neighbours think?

Step 15: Make a statement

The Palm Islands might be ridiculous, but who wouldn’t want to live in the world’s first inhabited volcano? When, in 2008, Norman Foster unveiled plans for a new city on an island on the outskirts of Moscow, the centrepiece was to be (at that point) the tallest building in the world: 450m high, covering almost half a million square metres and with a total floor area of 2.5 million square metres, housing theatres, exhibition spaces, 3,000 hotel rooms, 900 serviced apartments and a school. “Crystal Island is one of the world’s most ambitious building projects, and it represents a milestone in the 40-year history of the practice,” he said. But the economic crisis put paid to the grandiose scheme, which is perhaps a shame. After all, what’s the fun in building a new city if it doesn’t look cool?

Step 16: Treat workers with respect

In 2013, Nepalese migrants working in Lusail City in Qatar told the Guardian that their employers were making them work long hours in the heat and were withholding pay to keep them from running away. The International Trade Union Confederation estimates that 4,000 workers will die in Qatar by 2022. The country’s kafala system – where employers exercise broad power and influence over the lives of their workers – has been called modern-day slavery by human rights watchers. It doesn’t have to be this way. Building a new city from scratch can be socially beneficial. For instance, perhaps one of at the most heartening features about the Palestinian new city of Rawabi is that one third of its engineers and architects are women, a gender balance without precedent in the Arab world.

Step 17: Build fast. No, faster …

Egypt’s new capital city, according to the developers’ brochure, will have exactly 21 residential districts housing 5 million residents, span 700 sq km (a space almost as big as Singapore), with 663 hospitals and clinics, 1,250 mosques and churches, and 1.1m homes. Oh yes, and –according to the brochure – it will be built within the next five to seven years. No pressure.

Step 18: Re-educate your new urbanites

In Kangabashi, a new city for one million people in the Ordos region of Inner Mongolia, China, new residents are handed a welcome pack that includes fans and a list of instructions: “Don’t spit, don’t throw rubbish on the streets, don’t play loud music, don’t drive on the pavement,” says the introductory brochure. The thinking is that most of the residents are country dwellers from nearby villages who don’t know how to behave in cities. I know what you’re thinking: when are the urbanites of London, New York and Paris going to get forcibly re-educated so they don’t continue to befoul their built environment with their phlegm and unspeakable music?

When work started on Kangbashi five years ago, it was derided as a “ghost city”. But rural workers are now indeed moving into the city’s new high-rises, lured by generous compensation packages. The Chinese authorities’ idea is that such cities help diversify the country’s economy: subsistence farming was becoming less economically worthwhile, owing to poor soils and increasing water shortages. The enormous wealth of the region’s coal industry helped pay for much of the city’s infrastructure, and there was cheap land to build on. Kangbashi is just the beginning: a test run for Beijing’s plans to urbanise the vast rural interior of China, and relocate 250 million farmers over the next two decades – a social experiment as much as an economic one.

Step 19: If you build it, they will come

As any planner knows, it doesn’t matter how sophisticated your 3D-imaging software or how smart your urban vision. “The test will be when the hookers come there, when the gay pride parade is flagged off on the promenade, and an organisation of deviants has its annual convention in town,” Ajit Gulabchand, the developer of Lavasa, has said. “I don’t want to plan for that, but I’ll be happy if it happens.” Quite so: one of the pleasures of creating a city from scratch must surely be that it goes rogue and becomes something other than you imagined.

Step 20: Oh, yes – give it a name

The planned new capital of Egypt doesn’t yet have a name, though the safe money says it won’t be called Mubarakville, Cairo 2.0 or Sisi City – though I kind of like the last one. And what of the new city rising on the coast of the Red Sea? It has a lot of things going for it. It will house one of the largest sea ports in the world. It will provide more than a million jobs. And, if construction sticks to schedule, it will be complete by 2020. Only one problem: its called King Abdullah Economic City. Perhaps it sounds nicer in Arabic.

This feature is written by Stuart Jeffries and adapted from The Guardian.