Drought has been deadly for indigenous people in Colombia’s desert peninsula, underscoring a global crisis: People will be forced from their homes as weather turns more extreme.

PHOTOGRAPH BY FERNANDO VERGARA, ASSOCIATED PRESS

PORCIOSA, Colombia—Seventeen-year-old Virginia Pushaina drops an orange bucket into the murky depths of an open pit to collect muddy water. It’s early morning in October, but the temperature’s already approaching 90 degrees. Crops of corn and beans have long since shriveled to dust, and emaciated goats scrounging for food in the sand no longer can feed a family or fetch a good price at market.

Six months pregnant, Pushaina often thinks about the baby son she lost to an infection two years ago. She now fears for her young daughter, who often lacks clean water and receives little nourishment apart from a few swallows of chicha, a fermented corn drink.

Since the region’s crippling drought began three years ago, 12 children among Pushaina’s hundred extended family members have died from malnutrition, dehydration, or illnesses caused by consuming dirty, stagnant water from the earthen wells. Many mothers in this indigenous Wayúu community on the Caribbean desert peninsula of Guajira are so malnourished that they are unable to produce milk for their babies.

PHOTOGRAPH BY FERNANDO VERGARA, ASSOCIATED PRESS

Long before dawn breaks, women from the ranchería of Porciosa set out into the night with battered plastic containers, walking for hours across the sweltering desert to retrieve clean water from the nearest potable wells. They haul it back by burro or on bicycles, or lacking those, they carry it themselves. If they can’t carry enough to meet their families’ needs, they must resort to consuming water from Porciosa’s two pit wells, which are contaminated with bacteria. It’s an arduous daily ritual carried out in Wayúu rancherías, or settlements, across the state of La Guajira.

From our partners:

The word víctima in Colombia has a strong association with the country’s long-running armed conflict. But as the Colombian government moves steadily toward a peace accord, it is grappling with how to respond to a new kind of victim—people forced from their homes as they suffer the effects of higher temperatures, rising sea levels, and more extreme droughts and floods.

The Wayúu’s plight underscores a broader challenge for Colombia: analyzing the climate-related tipping points that could make people already suffering poverty, conflict, or other environmental threats more likely to migrate, particularly to its crowded cities.

It’s an emerging concern all around the world, yet consensus on the best ways forward remains elusive. When the United Nations climate talks commence in Paris on November 30, climate-related migration is likely to garner only a small amount of space in the accord’s text. That leaves individual countries to devise their own approaches to measuring migration and displacement and safeguarding rights.

Worldwide an average of 22.5 million people have been displaced each year since 2008 by natural disasters related to extreme weather and climate change, according to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, part of the Norwegian Refugee Council.

“We are moving beyond the social conflict already occurring in the country toward a different vulnerability, and some of those [affected] people have no recognition and no future unless we try to understand what’s happening with migration,” says Elsa Garcia Salazar, an environmental monitor specializing in climate change at the Bogotá office of the International Organization for Migration.

Crisis in La Guajira

For centuries, the Wayúu have resourcefully adapted to seasonal dry periods by migrating within their territory, which extends across the border to Venezuela. But the region’s unprecedented drought is exacerbating the effects of armed conflict, environmental degradation, and government neglect, driving many in this tribe of some 400,000 to a point of crisis.

“It’s very critical, the situation of our community,” says Arico Pushaina, a community leader in Porciosa. “If the government doesn’t help us … the Wayúu will come to an end in this land.”

Scientists at IDEAM, Colombia’s institute of hydrology and meteorology, attribute Guajira’s three-year drought to repeated El Niños, a weather phenomenon causing hot and dry conditions there. But recent research says the frequency of these extreme El Niño events has increased due to global warming. And with more intense droughts predicted for this region, the fate of the people who call this windswept desert home remains uncertain.

PHOTOGRAPH BY AUTUMN SPANNE

Across Guajira Peninsula’s 9,700 square miles, a staggering 37,000 people suffer from malnutrition, according to a 2014 report by Colombia’s Ombudsman Office. Its hunger crisis intensified in August, when Venezuela closed its border and imposed strict checkpoints to fight contraband gasoline, food, and other products flowing into Colombia. Since then, the Wayúu have found it harder to get cheaper Venezuelan goods, making a bad economy even worse.

The drought also is exacerbating another serious water woe: the damming of the Río Ranchería, the main river that flows through La Guajira. The river was dammed in large part to quench the voracious thirst of mining companies, resulting in its flow being cut off from the Wayúu. The Wayúu are now petitioning the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights to restore their access.

No one in Porciosa has yet migrated outside of traditional Wayúu territory. But in nearby communities, some—particularly younger people—have left for other Colombian states, according to local leaders.

PHOTOGRAPH BY AUTUMN SPANNE

Garcia wants to know whether the drought is altering the Wayúu’s traditional migration patterns and pushing them in greater numbers toward urban areas and neighboring states. There’s an urgent need, she says, for rigorous data collection tools that can aid policymakers in understanding how phenomena linked to climate change are contributing to human migration—not only in La Guajira but throughout the country.

One study ranks Colombia 18th in the world for climate change risks—two to three times the risk of neighboring Brazil, Venezuela, and Ecuador: From expansive agricultural lands to urban centers in the Andes to nearly 2,000 miles of coastline, the majority of Colombians live in places likely to be affected by extreme weather, sea level rise, and other phenomena exacerbated by global warming.

[infobox title=’Rodrigo Suárez Castaño, director of the climate change division at Colombia’s Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development said:’]“If the government doesn’t help us … the Wayúu will come to an end in this land.”

“We have a lot of challenges with climate change issues.” “If things keep going this way, we’re going to have more people moving and more people living in cities. It’s a big question and challenge we have on our hands.”

[/infobox]

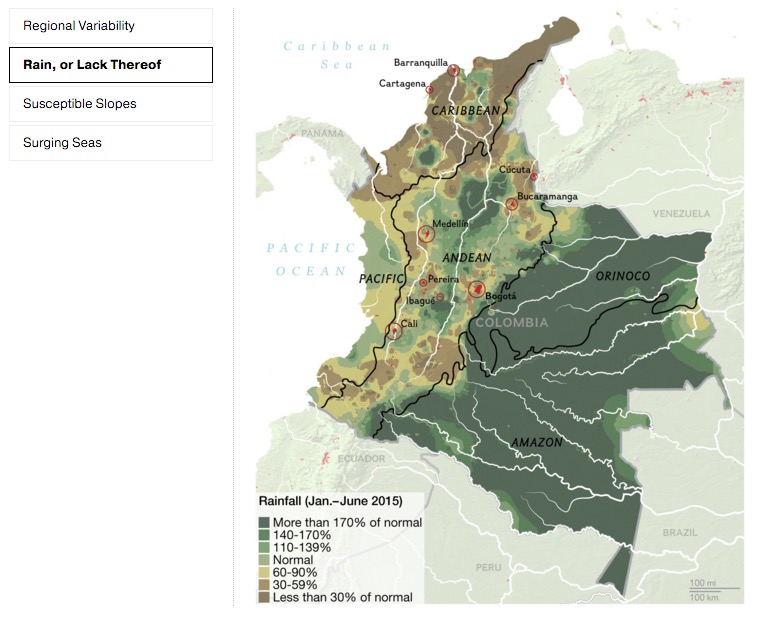

Colombia’s Climate Challenges

Colombia is being hit by climate-related changes that are exacerbating underlying problems, driving thousands from their homes.

Colombia’s Wake-up Call

Last year, Colombia became one of the first countries in South America to include migration in its national climate change adaptation plan.

PHOTOGRAPH BY FERNANDO VERGARA, ASSOCIATED PRESS

A pivotal event for the Colombian government in recognizing the potential for climate-induced migration was the devastating, widespread La Niña floods in 2010 and 2011, which affected more than three million people throughout the country. There is no clear data on how many people were ultimately displaced, but flooding and mudslides damaged nearly 500,000 homes and affected millions of acres of agricultural lands.

IT WAS A WAKE-UP CALL. Following the floods, the government collaborated with the International Organization for Migration to track 2,000 people who had been displaced—an initial step toward a national climate migration study. The survey revealed trends similar to those seen in conflict displacement. Two years after the floods, nearly half had not yet returned home. Many had migrated to large cities like Medellín, Bogotá, and Cartagena.

“If you don’t have something in the Paris outcome, it will be much more difficult to keep [migration] on the list of priorities.”

~ WALTER KAELIN ~

Nansen Initiative

Like those displaced by conflict, people displaced by the flooding lost property, income, and social support networks. They often settled informally on the fringe of cities in undesirable areas lacking basic infrastructure. People arriving from rural agricultural regions also tended to lack skills necessary to find jobs in an urban economy.

The small study underscored that cities need to be prepared to receive new migrants as part of their own climate adaptation plans. So far, they lack systems for preparing for them.

PHOTOGRAPH BY FERNANDO VERGARA, ASSOCIATED PRESS

Can the Cities Cope?

Take the Colombian city of Cartagena. The city is home to tens of thousands of displaced conflict victims, many of whom settle informally along the major coastal lagoon of Cienaga de la Virgen with no sewer, water, or other municipal services. The arrival of more people because of climate-related phenomena—like flooding to the city’s south, rising seas that threaten the islands off its coast, and drought in La Guajira—will add to the pressures.

But while Cartagena has one of the most advanced adaptation plans in the region, the city hasn’t yet developed a strategy for climate migration. Suárez says the national government is supporting such efforts by providing guidelines.

“We are moving beyond the social conflict already occurring in the country toward a different vulnerability.”

~ ELSA GARCIA SALAZAR ~

International Organization for Migration

[infobox title=’Dolly González, Cartagena’s city planning director said:’]

“If we don’t make a commitment to getting solid data about patterns of climate migration, we will not have adequate tools for decision-making.” “People who arrive in Cartagena because of climate change are staying outside of the government aid programs, because the focus has been conflict.”

[/infobox]

Beyond counting and tracking migrants, governments face challenges in developing legal mechanisms to provide ongoing support after initial crises like floods and fires. In Colombia, those fleeing extreme weather aren’t covered by the same laws that protect the rights of conflict-displaced migrants. So far, there isn’t even a standardized international definition of what constitutes a climate migrant.

PHOTOGRAPH BY FERNANDO VERAGARA, ASSOCIATED PRESS

The big question now is whether migration and displacement will be included in a new UN climate accord. Ahead of Paris, some developing nations proposed a new entity to organize humanitarian responses to climate-related disasters.

There’s general agreement that climate migration will grow in coming decades, notes Walter Kaelin of the Nansen Initiative, which is working to improve international responses to people displaced by natural disasters. But providing compensation for affected countries is a sticking point. “If you don’t have something in the Paris outcome, it will be much more difficult to keep this on the list of priorities,” he says.

A Plea to Preserve a Culture

Back in Porciosa, Virginia Pushaina watches her 19-month-old daughter grow weak and cry for food. She notices that the toddler has the same skin rash that her son developed before contracting a fatal infection. But she doesn’t have much time to dwell on such unsettling thoughts. Each day she must give herself completely to the present: tending her daughter, walking miles to fetch water, and making mochilas, intricately-woven cotton bags popular with tourists that have become crucial to the economic survival of many Wayúu families.

“If things keep going this way, we’re going to have more people moving and more people living in cities.”

~ RODRIGO SUAREZ CASTANO~

Colombia Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development

Arico Pushaina pleads for greater government investment, including deeper wells, new windmills and solar pumps, medical clinics, and programs that allow artisans to get a fairer price for their goods.

He worries that, if La Guajira’s droughts become more intense and prolonged, the young will no longer be able to rely on traditional economic activities such as livestock and subsistence agriculture. What future will the Wayúu have, he wonders, if they are forced to leave for crime-ridden cities, far removed from their culture?

PHOTOGRAPH BY AUTUMN SPANNE

His uncertainty about the future also stems from another source. Contaminated water has contributed to the death of ten elders since the drought began, says Pushaina. With them goes their precious cultural knowledge, including the Wayúu tradition of using dreams to plan for the future.

“When they interpret dreams, they inform the community about what’s to come. It has really affected us, the [loss of] elders,” he says. “We no longer know what’s going to happen.”

This feature originally appeared in National Geographic.