An analysis of once-rejected, later-constructed routes in Los Angeles, Atlanta, and Houston.

Houston, Atlanta, and Los Angeles are three of America’s most notoriously car-dependent metropolitan areas, but each has taken steps of late to counter highway-first development patterns with more sustainable ones. Houston is expanding its light rail system, improving walkability, and considering an enhanced bus plan. Atlanta has pushed transit-oriented development with its BeltLine project and may soon add a new county to its MARTA system. Los Angeles remains committed to a 30-year, transit-intensive, multi-modal plan funded by voters in 2008.

The transportation futures of these cities will largely be defined by whether these new efforts pan out or fall flat. Before elected officials and transportation authorities in these cities look too far ahead, they might be wise to glance back. During the past 50 years, citizens in Houston, Atlanta, and Los Angeles rejected transit plans only to see elements of those same plans re-emerge in today’s growing systems. By delaying the development of mass transit within their most densely populated corridors, in some cases for decades, all three cities missed opportunities to expand mobility, contributing to many of the problems they face today.

To illustrate this point, I’ve undertaken an analysis of historic transit maps from each of these cities to highlight many of these once-rejected, later-constructed routes.

From our partners:

Los Angeles

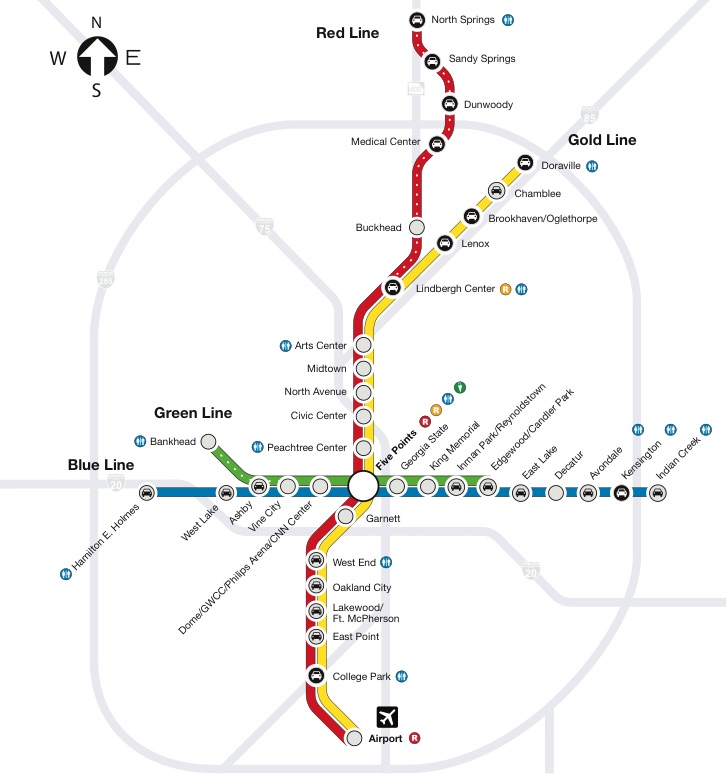

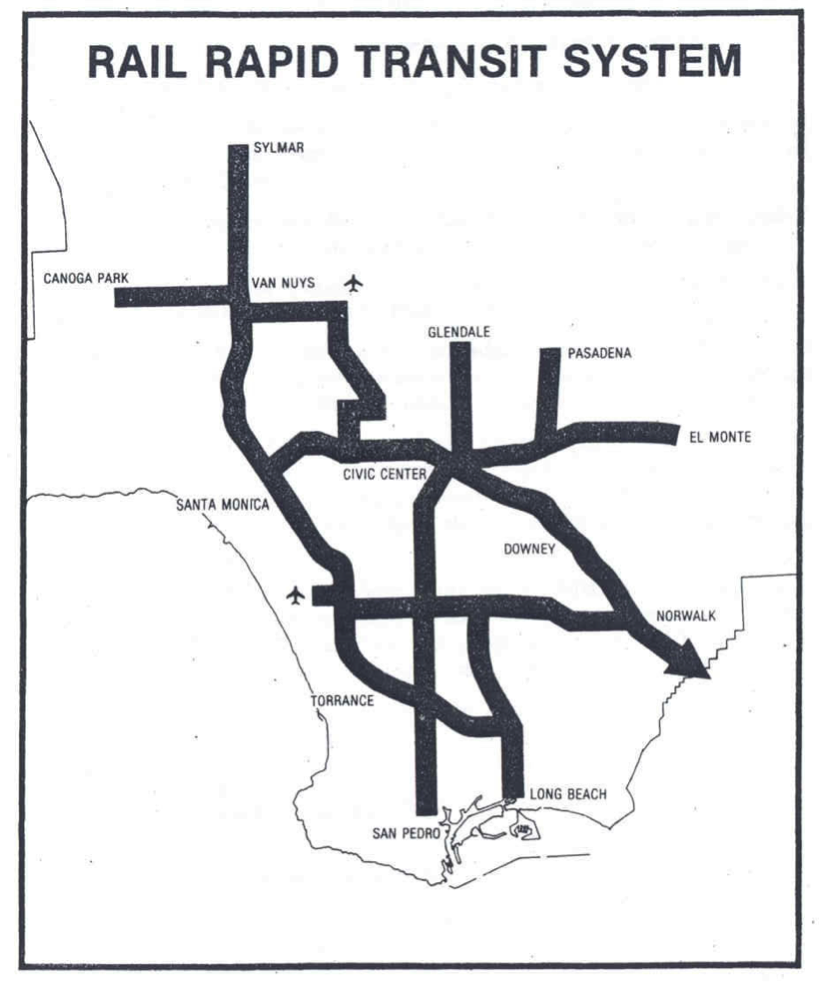

Below you’ll find a transit plan from Los Angeles from 1968 that shows one of L.A.’s first major public transit proposals. Forwarded by the Southern California Rapid Transit District in 1968, the plan called for the construction of five inaugural transit lines. Spiraling outward from a hub downtown, these heavy rail lines included routes north through Hollywood toward the San Fernando Valley, south to Long Beach, southwest to LAX airport, west down Wilshire Boulevard, and east toward El Monte.

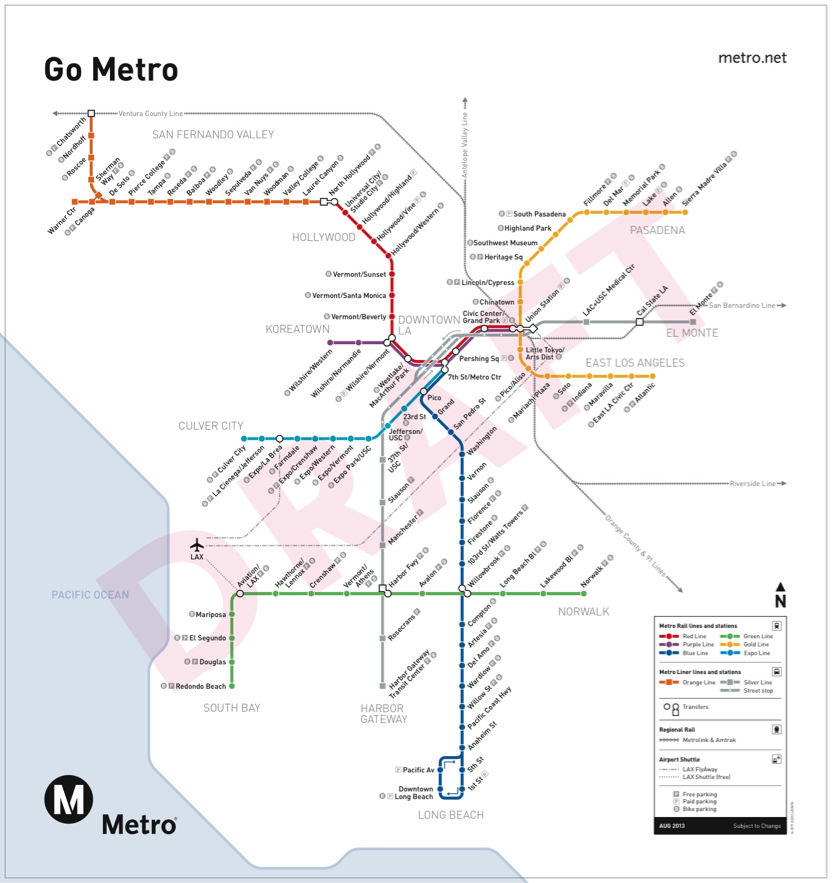

Voters rejected the plan for a variety of reasons. Some viewed the explicit routing and station locations as threats to their communities, while suburban residents didn’t want to pay higher taxes for poor service. In the 1970s, L.A. voters rejected two other plans with similar route proposals for comparable reasons. Finally, in 1980, a plan that mirrored the previously rejected routes was accepted (below). Voters found the plan’s more abstract “corridors” proposal less threatening and approved of its promise to provide nearly equal support to rail, bus, and road improvements. Two lines that would run along the same paths as the 1968 proposal, the line from downtown (Civic Center) to Long Beach and the line from Santa Monica to downtown, received priority.

Today, L.A. has just over 90 miles of operating rail lines—both subway and light rail—and another 42 miles of BRT lines. The majority of these lines (below) appeared on the first rail map nearly forty years ago. The blue (south to Long Beach), the purple (west to Wilshire), and red lines (north to Hollywood) appear within nearly the exact corridors as earlier plans, and the orange and silver line BRTs serve corridors highlighted in the initial rail plan. Future expansions are already funded by Proposition R, which passed in 2008. While the city still faces massive traffic problems on its freeways, the system L.A. has and will continue to develop allows the region to move forward with a full complement of options—albeit decades after that process might have begun.

Atlanta

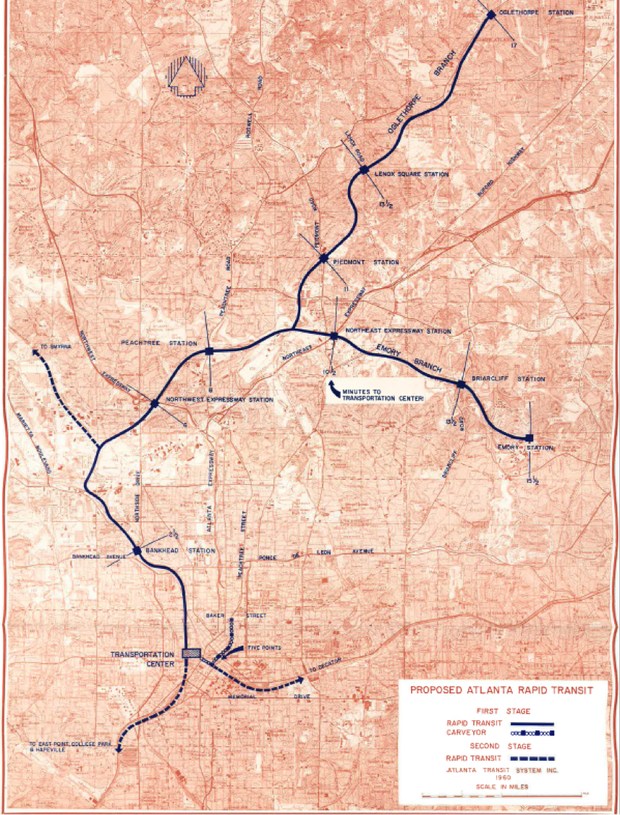

Atlanta’s transit proposals demonstrate how sustained suburban resistance to a transit system can alter the long-term development of a region. An early transit map (below), created in 1960 by the private company Atlanta Transit System, Inc., proposed a rapid rail system that would run from a “Transportation Center” in downtown Atlanta towards Oglethorpe in the north and Emory University in the northeast. The initial phase limited the system to Fulton and DeKalb counties. A proposed second stage would have brought service to the edge of Cobb County to the northwest and Clayton County to the south. Gwinnett County, to the northeast, was not included in either phase. Atlanta Transit Inc. hoped the plan would convince the State of Georgia to make it the operator of the city’s first public transit authority.

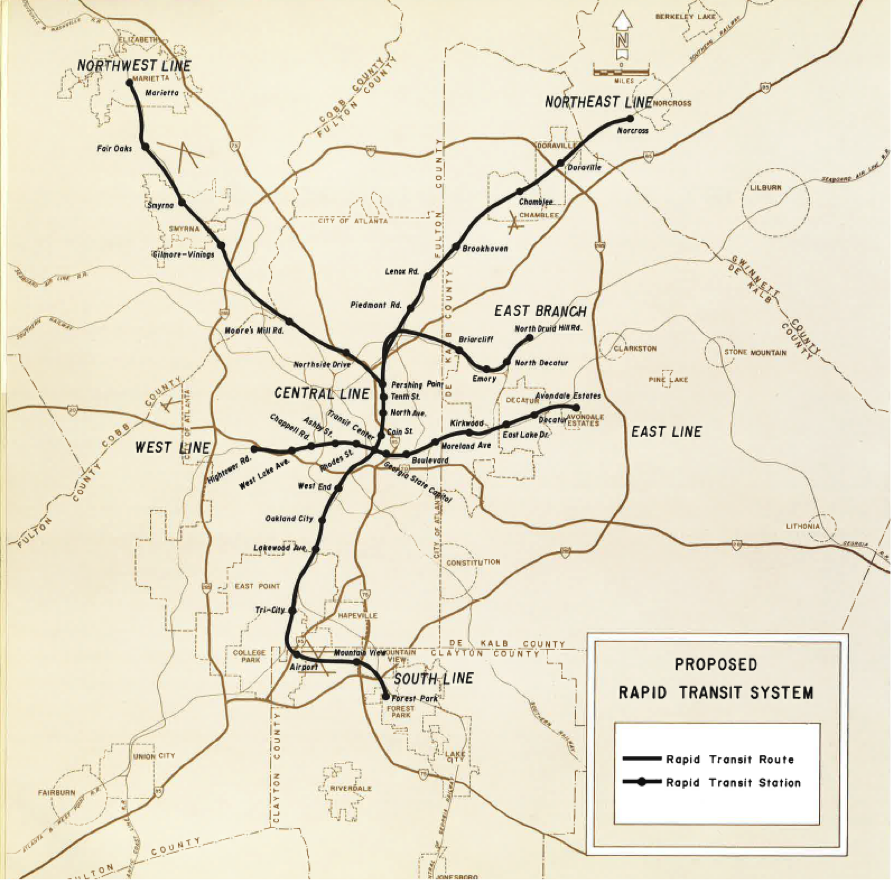

The state of Georgia did not take Atlanta Transit Inc. up on their proposal. The company went bankrupt in the mid-1960s prior to the state creating the Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority (MARTA) in 1965. MARTA’s first formal proposal, produced by the engineering firm Parsons Brinckerhoff-Tudor-Bechtel in 1967, built upon the private company’s earlier plans. In addition to the routes toward Decatur and Oglethorpe (De Kalb County) and parallel to Interstate 20 past Clark Atlanta University in Fulton County, the plan added full routes to Marietta in Cobb County, Norcross in Gwinnett County, and to Forest Park in Clayton County.

A dearth of service to African-American neighborhoods, and suburban fears about higher taxes and a possible influx of black Atlantans into predominately white communities, contributed to the defeat of the 1968 plan in all five metro-area counties. MARTA quickly added more stations to predominately black parts of the city and repackaged a citizen-influenced plan for a vote in 1971. Voters in Fulton and DeKalb counties approved the new iteration, but suburbanites in Cobb, Gwinnett, and Clayton voted against joining.

The effects of that outcome are visible on the current MARTA rail map (below). Today, while Atlanta’s rail lines serve much of Fulton and DeKalb counties, the proposed suburban routes stop at the boundaries of non-participating counties (with the exception of the yellow and red lines to the airport, which sits mostly in Clayton County). Suburban resistance to joining MARTA has created a complicated network of transportation agencies and forced officials to build larger road networks to adequately serve suburban areas. But there is hope of progress: Clayton County voted to place a one-cent sales tax on the ballot, that, if passed, would add the county to the MARTA service area and open the possibility of bringing bus service and a rail line into the county, as first proposed in 1967.

Houston

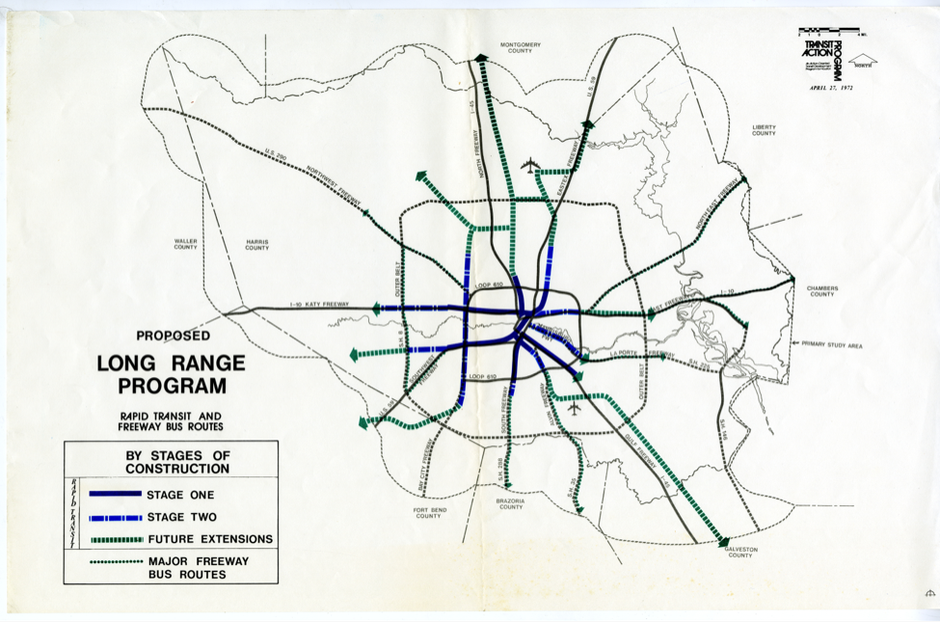

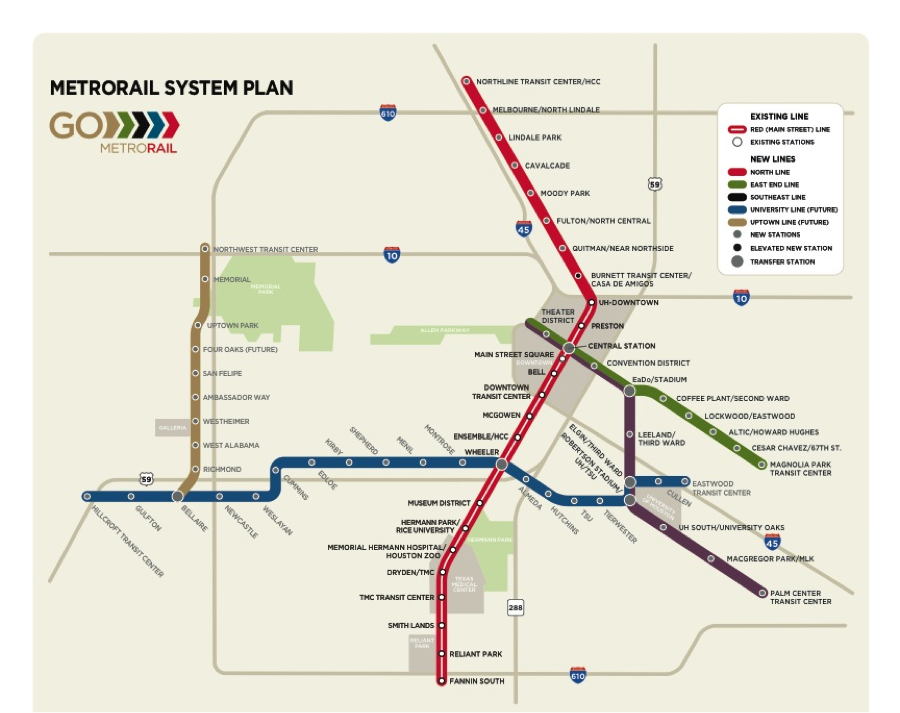

Houston’s unrealized transit plans show the missed opportunities of past referendums even more than those of L.A. or Atlanta. A 1973 proposal for a mass transit authority and a transit system (below) laid out a substantial network of rails and busways along the city’s highways. Despite early support from officials, failure to consult any major constituencies led to the referendum’s rejection. As we’ll see in the modern map in a moment, four of today’s existing or planned light rail routes follow those laid out in the 1973 plan.

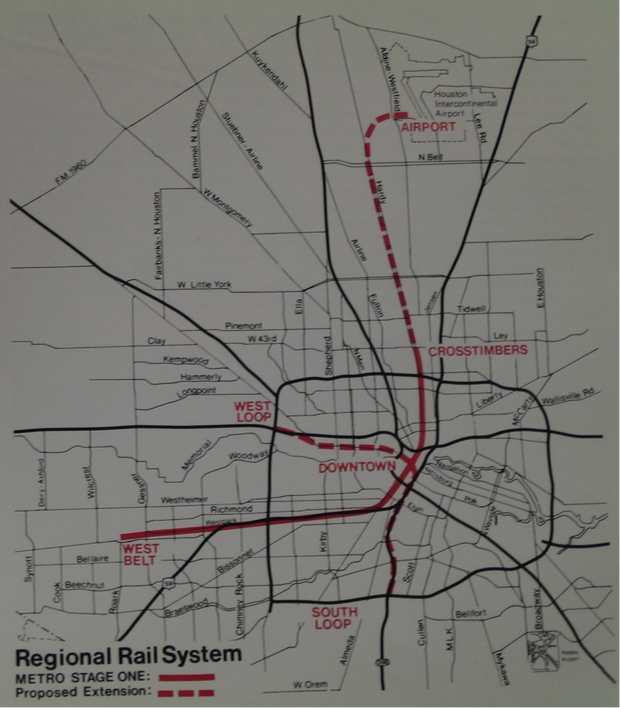

In 1983, Houston’s fledgling transit agency, METRO, released its first major transit plan since its creation in 1978 (below). While it proposed a smaller total system, the first stages tracked over those in earlier plans for Highway 59 (west belt), downtown, and the airport. This proposal was defeated primarily because of suburban resistance. After its defeat, metropolitan voters approved a county toll road authority that eventually built two tollways through the west belt and airport corridors, all but precluding later rail development in those areas.

Now take a look at Houston’s current light rail map (below). It makes clear that the rejection of earlier plans didn’t eliminate them—but merely delayed the construction of routes that have remained relatively unchanged for 30 years. The north line began service in 2013 and extended Houston’s inaugural red line, which opened in 2004, along nearly the same path as one proposed in the 1973 plan. Both the historic proposal and current day line run north from downtown on the east side of Interstate 45 and extend just beyond Interstate 610. Today’s blue line remains close to the Highway 59/west belt path laid out in the two preceding plans. Both the green and purple lines (slated to open in 2015) mirror those proposed in 1973. The brown line follows the same path as a spur proposed in a 1980 plan.

But in a case of history repeating itself, in a divisive and unclear 2012 referendum, Houstonians placed funding for the blue and brown lines on hold. While a BRT system will replace the brown line and bring a measure of transit improvement to the area, the vote delayed overall improvement of transit by compromising the cohesion of the rail system and redoubling Houston’s reliance on highways.

Now, the construction of more rail lines in Houston, Atlanta, or Los Angeles over the previous 30 years would not have miraculously solved all the issues caused by traffic congestion, population growth, or urbanization. (Indeed, as traffic jams in L.A. attest, even a formidable mass transit network cannot meet all growth demands.) Nor are trains alone a transportation panacea. All three cities have effective, if at-capacity, suburban bus systems that will play crucial roles in the creation of successful regional transit.

But the lesson is that historic transportation decisions offer evidence to support citizens, elected officials, and transit authorities making bold decisions about regional transportation in the present—sometimes even before travel demand exists—that will pay dividends in the future. Time and again, American cities have chosen to embrace road construction and neglected to fund mass transit at anywhere near the same level. As the nation’s highway network once again faces what seems to be a now annual funding crisis and calls for state and local funding of new projects grow, ensuring that municipalities and metropolitan areas reflect upon the historic paths that have brought them to the present day and what choices made today might mean for tomorrow has never been more timely or essential.

This article is written by Kyle Shelton & originally appeared in CityLab.