This is a classic article by Jane Jacobs originally published in Fortune Magazine in 1958.

If the downtown of tomorrow looks like most of the redevelopment projects being planned for it today, it will end up a monumental bore. But downtown could be made lively and exciting — and it’s not too hard to find out how.

This year is going to be a critical one for the future of the city. All over the country civic leaders and planners are preparing a series of redevelopment projects that will set the character of the center of our cities for generations to come. Great tracts, many blocks wide, are being razed; only a few cities have their new downtown projects already under construction; but almost every big city is getting ready to build, and the plans will soon be set.

What will the projects look like? They will be spacious, parklike, and uncrowded. They will feature long green vistas. They will be stable and symmetrical and orderly. They will be clean, impressive, and monumental. They will have all the attributes of a well-kept, dignified cemetery. And each project will look very much like the next one: the Golden Gateway office and apartment center planned for San Francisco; the Civic Center for New Orleans; the Lower Hill auditorium and apartment project for Pittsburgh; the Convention Center for Cleveland; the Quality Hill offices and apartments for Kansas City; the downtown scheme for Little Rock; the Capitol Hill project for Nashville. From city to city the architects’ sketches conjure up the same dreary scene; here is no hint of individuality or whim or surprise, no hint that here is a city with a tradition and flavor all its own.

From our partners:

These projects will not revitalize downtown; they will deaden it. For they work at cross-purposes to the city. They banish the street. They banish its function. They banish its variety. There is one notable exception, the Gruen plan for Fort Worth; ironically, the main point of it has been missed by the many cities that plan to imitate it. Almost without exception the projects have one standard solution for every need: commerce, medicine, culture, government—whatever the activity, they take a part of the city’s life, abstract it from the hustle and bustle of downtown, and set it, like a self-sufficient island, in majestic isolation.

There are, certainly, ample reasons for redoing downtown–falling retail sales, tax bases in jeopardy, stagnant real-estate values, impossible traffic and parking conditions, failing mass transit, encirclement by slums. But with no intent to minimize these serious matters, it is more to the point to consider what makes a city center magnetic, what can inject the gaiety, the wonder, the cheerful hurly-burly that make people want to come into the city and to linger there. For magnetism is the crux of the problem. All downtown’s values are its byproducts. To create in it an atmosphere of urbanity and exuberance is not a frivolous aim.

We are becoming too solemn about downtown. The architects, planners—and businessmen–are seized with dreams of order, and they have become fascinated with scale models and bird’s-eye views. This is a vicarious way to deal with reality, and it is, unhappily, symptomatic of a design philosophy now dominant: buildings come first, for the goal is to remake the city to fit an abstract concept of what, logically, it should be. But whose logic? The logic of the projects is the logic egocentric children, playing with pretty blocks and shouting “See what I made!”–a viewpoint much cultivated in our schools of architecture and design. And citizens who should know better are so fascinated by the sheer process of rebuilding that the end results are secondary to them.

With such an approach, the end results will be about as helpful to the city as the dated relics of the City Beautiful movement, which in the early years of this century was going to rejuvenate the city by making it parklike, spacious, and monumental. For the underlying intricacy, and the life that makes downtown worth fixing at all, can never be fostered synthetically. No one can find what will work for our cities by looking at the boulevards of Paris, as the City Beautiful people did; and they can’t find it by looking at suburban garden cities, manipulating scale models, or inventing dream cities.

You’ve got to get out and walk. Walk, and you will see that many of the assumptions on which the projects depend are visibly wrong. You will see, for example; that a worthy and well-kept institutional center does not necessarily upgrade its surroundings. (Look at the blight-engulfed urban universities, or the petered-out environs of such ambitious landmarks as the civic auditorium in St. Louis and the downtown mall in Cleveland.) You will see that suburban amenity is not what people seek downtown. (Look at Pittsburghers by the thousands climbing forty-two steps to enter the very urban Mellon Square, but balking at crossing the street into the ersatz suburb of Gateway Center.)

[infobox]There is no logic that can be superimposed on the city; people make it, and it is to them, not buildings, that we must fit our plans.[/infobox]You will see that it is not the nature of downtown to decentralize. Notice how astonishingly small a place it is; how abruptly it gives way, outside the small, high-powered core, to underused area. Its tendency is not to fly apart but to become denser, more compact. Nor is this tendency some leftover from the past; the number of people working within the cores has been on the increase, and given the long-term growth in white-collar work it will continue so. The tendency to become denser is a fundamental quality of downtown and it persists for good and sensible reasons.

If you get out and walk, you see all sorts of other clues. Why is the hub of downtown such a mixture of things? Why do office workers on New York’s handsome Park Avenue turn off to Lexington or Madison Avenue at the first corner they reach? Why is a good steak house usually in an old building? Why are short blocks apt to be busier than long ones?

It is the premise of this article that the best way to plan for downtown is to see how people use it today; to look for its strengths and to exploit and reinforce them. There is no logic that can be superimposed on the city; people make it, and it is to them, not buildings, that we must fit our plans. This does not mean accepting the present; downtown does need an overhaul, it is dirty, it is congested. But there are things that are right about it too, and by simple old-fashioned observation we can see what they are. We can see what people like.

How hard can a street work?

The best place to look at first is the street. One had better look quickly too; not only are the projects making away with the noisy automobile traffic of the street, they are making away with the street itself. In its stead will be open spaces with long vistas and lots and lots of elbowroom.

But the street works harder than any other part of downtown. It is the nervous system; it communicates the flavor, the feel, the sights. It is the major point of transaction and communication. Users of downtown know very well that downtown needs not fewer streets, but more, especially for pedestrians. They are constantly making new, extra paths for themselves, through mid-block lobbies of buildings, block-through stores and banks, even parking lots and alleys. Some of the builders of downtown know this too, and rent space along their hidden streets.

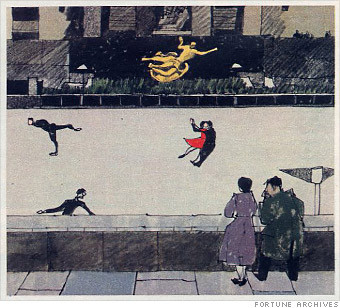

Rockefeller Center, frequently cited to prove that projects are good for downtown, differs in a very fundamental way from the projects being designed today. It respects the street. Rockefeller Center knits tightly into every street that intersects it. One of its most brilliant features is the full-fledged extra street with which it cuts across blocks that elsewhere are too long. Its open spaces are eddies of the streets, small and sharp and lively, not large, empty, and boring. Most important, it is so dense and concentrated that the uniformity it does possess is a relatively small episode in the area.

As one result of its extreme density, Rockefeller Center had to put the overflow of its street activity underground, and as is so often the case with successful projects, planners have drawn the wrong moral: to keep the ground level more open, they are sending the people into underground streets although the theoretical purpose of the open space is to endow people with more air and sky, not less. It would be hard to think of a more expeditious way to dampen downtown than to shove its liveliest activities and brightest lights underground, yet this is what Philadelphia’s Penn Center and Pittsburgh’s Gateway Center do. Any department-store management that followed such a policy with its vital ground-floor space, instead of using it as a village of streets, would go out of business.

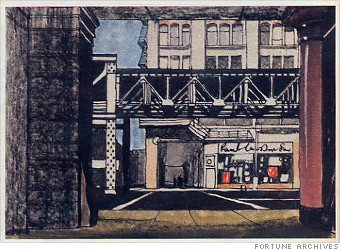

The animated alley

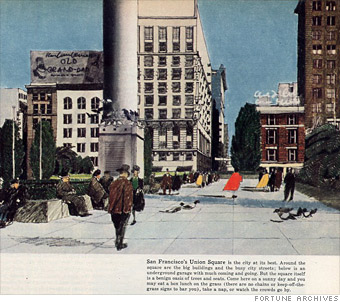

The real potential is in the street, and there are far more opportunities for exploiting it than are realized. Consider, for example, Maiden Lane, an odd two-block-long, narrow, back-door alley in San Francisco. Starting with nothing more remarkable than the dirty, neglected back sides of department stores and nondescript buildings, a group of merchants made this alley into one of the finest shopping streets in America. Maiden Lane has trees along its sidewalks, redwood benches to invite the sightseer or window shopper or buyer to linger, sidewalks of colored paving, sidewalk umbrellas when the sun gets hot. All the merchants do things differently: some put out tables with their wares, some hang out window boxes and grow vines. All the buildings, old and new, look individual; the most celebrated is an expanse of tan brick with a curved doorway, by architect Frank Lloyd Wright. The pedestrian’s welfare is supreme; during the rush of the day, he has the street. Maiden Lane is an oasis with an irresistible sense of intimacy, cheerfulness, and spontaneity. It is one of San Francisco’s most powerful downtown magnets.

Downtown can’t be remade into a bunch of Maiden Lanes; and it would be insufferably quaint if it were. But the potential illustrated can be realized by any city and in its own particular way. The plan by Victor Gruen Associates for Fort Worth is an outstanding example. It has been publicized chiefly for its arrangements to provide enormous perimeter parking garages and convert the downtown into a pedestrian island, but its main purpose is to enliven the streets with variety and detail. This is a point being overlooked by most of the eighty-odd cities that, at last count, were seriously considering emulation of the Gruen plan’s traffic principles.

There is no magic in simply removing cars from downtown, and certainly none in stressing peace, quiet, and dead space. The removal of the cars is important only because of the great opportunities it opens to make the streets work harder and to keep downtown activities compact and concentrated. To these ends, the excellent Gruen plan includes, in its street treatment, sidewalk arcades, poster columns, flags, vending kiosks, display stands, outdoor cafes, bandstands, flower beds, and special lighting effects. Street concerts, dances, and exhibits are to be fostered. The whole point is to make the streets more surprising, more compact, more variegated, and busier than before-not less so.

One of the beauties of the Fort Worth plan is that it works with existing buildings, and this is a positive virtue not just a cost-saving expedient. Think of any city street that people enjoy and you will see that characteristically it has old buildings mixed with the new. This mixture is one of downtown’s greatest advantages, for downtown streets need high-yield, middling-yield, low-yield, and no-yield enterprises. The intimate restaurant or good steak house, the art store, the university club, the fine tailor, even the bookstores and antique stores–it is these kinds of enterprises for which old buildings are so congenial. Downtown streets should play up their mixture of buildings with all its unspoken–but well understood–implications of choice.

The smallness of big cities

It is not only for amenity but for economics that choice is so vital. Without a mixture on the streets, our downtowns would be superficially standardized, and functionally standardized as well. New construction is necessary, but it is not an unmixed blessing: its inexorable economy is fatal to hundreds of enterprises able to make out successfully in old buildings. Notice that when a new building goes up, the kind of ground-floor tenants it gets are usually the chain store and the chain restaurant. Lack of variety in age and overhead is an unavoidable defect in large new shopping centers and is one reason why even the most successful cannot incubate the unusual–a point overlooked by planners of downtown shopping-center projects.

We are apt to think of big cities as equaling big enterprises, little towns as equaling little enterprises. Nothing could be less true. Big enterprises do locate in big cities, but they find small towns as congenial. Big enterprises have great self-sufficiency, are capable of maintaining most of the specialized skills and equipment they need, and they have no trouble reaching a broad market.

But for the small, specialized enterprise, everything is reversed; it must draw on supplies and skills outside itself; its market is so selective it needs exposure to hundreds of thousands of people. Without the centralized city it could not exist; the larger the city, the greater not only the number, but the proportion, of small enterprises. A metropolitan center comes across to people as a center largely by virtue of its enormous collection of small elements, where people can see them, at street level.

The pedestrian’s level

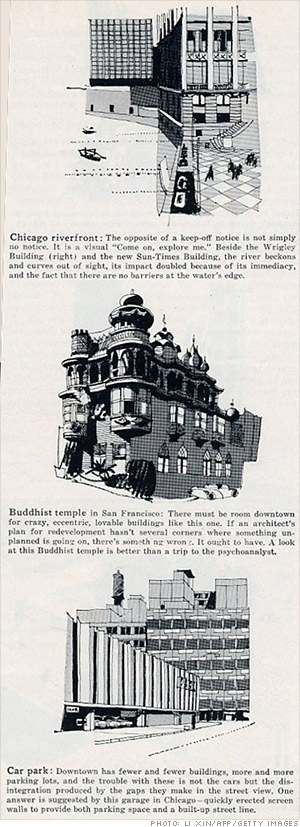

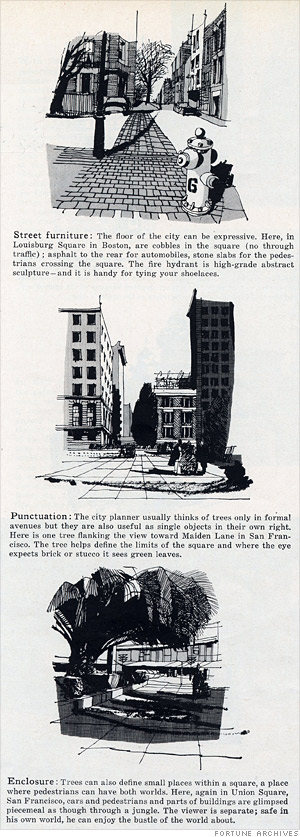

Let’s look for a moment at the physical dimensions of the street. The user of downtown is mostly on foot, and to enjoy himself he needs to see plenty of contrast on the streets. He needs assurance that the street is neither interminable nor boring, so he does not get weary just looking down it. Thus streets that have an end in sight are often pleasing; so are streets that have the punctuation of contrast at frequent intervals. Georgy Kepes and Kevin Lynch, two faculty members of M.I.T., have made a study of what walkers in downtown Boston notice. While the feature that drew the most comment was the proportion of open space, the walkers showed a great interest in punctuations of all kinds appearing a little way ahead of them–spaces, or greenery, or windows set forward, or churches, or clocks. Anything really different, whether large or a detail, interested them.

Narrow streets, if they are not too narrow (like many of Boston’s) and are not choked with cars, can also cheer a walker by giving him a continual choice of this side of the street or that, and twice as much to see. The differences are something anyone can try out for himself by walking a selection of downtown streets.

This does not mean all downtown streets should be narrow and short. Variety is wanted in this respect too. But it does mean that narrow streets or reasonably wide alleys have a unique value that revitalizers of downtown ought to use to the hilt instead of wasting. It also means that if pedestrian and automobile traffic is separated out on different streets, planners would do better to choose the narrower streets for pedestrians, rather than the most wide and impressive. Where monotonously wide and long streets are turned over to exclusive pedestrian use, they are going to be a problem. They will come much more alive and persuasive if they are broken into varying parts. The Gruen plan, for example, will interrupt the long, wide gridiron vistas of Fort Worth by narrowing them at some points, widening them into plazas at others. It is also the best possible showmanship to play up the streets’ variety, contrast, and activity by means of display windows, street furniture, imagination, and paint, and it is excellent drama to exploit the contrast between the street’s small elements and its big banks, big stores, big lobbies, or solid walls.

Most redevelopment projects cannot do this. They are designed as blocks: self-contained, separate elements in the city. The streets that border them are conceived of as just that–borders, and relatively unimportant in their own right. Look at the bird’s-eye views published of forthcoming projects: if they bother to indicate the surrounding streets, all too likely an airbrush has softened the streets into an innocuous blur.

Maps and reality

But the street, not the block, is the significant unit. When a merchant takes a lease he ponders what is across and up and down the street, rather than what is on the other side of the block. When blight or improvement spreads, it comes along the street. Entire complexes of city life take their names, not from blocks, but from streets–Wall Street, Fifth Avenue, State Street, Canal Street, Beacon Street.

Why do planners fix on the block and ignore the street? The answer lies in a short cut in their analytical techniques. After planners have mapped building conditions, uses, vacancies, and assessed valuations, block by block, they combine the data for each block, because this is the simplest way to summarize it, and characterize the block by appropriate legends. No matter how individual the street, the data for each side of the street in each block is combined with data for the other three sides of its block. The street is statistically sunk without a trace. The planner has a graphic picture of downtown that tells him little of significance and much that is misleading.

Believing their block maps instead of their eyes, developers think of downtown streets as dividers of areas, not as the unifiers they are. Weighty decisions about redevelopment are made on the basis of what is a “good” or “poor” block, and this leads to worse incongruities than the most unenlightened laissez faire.

The Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts in New York is a case in point. This cultural superblock is intended to be very grand and the focus of the whole music and dance world of New York. But its streets will be able to give it no support whatever. Its eastern street is a major trucking artery where the cargo trailers, on their way to the industrial districts and tunnels, roar so loudly that sidewalk conversation must be shouted. To the north, the street will be shared with a huge, and grim, high school. To the south will be another superblock institution, a campus for Fordham.

And what of the new Metropolitan Opera, to be the crowning glory of the project? The old opera has long suffered from the fact that it has been out of context amid the garment district streets, with their overpowering loft buildings and huge cafeterias. There was a lesson here for the project planners. If the published plans are followed, however, the opera will again have neighbor trouble. Its back will be its effective entrance; for this is the only place where the building will be convenient to the street and here is where opera-goers will disembark from taxis and cars. Lining the other side of the street are the towers of one of New York’s bleakest public-housing projects. Out of the frying pan into the fire.

If redevelopers of downtown must depend so heavily on maps instead of simple observation, they should draw a map that looks like a network, and then analyze their data strand by strand of the net, not by the boles in the net. This would give a picture of downtown that would show Fifth Avenue or State Street or Skid Row quite clearly. In the rare cases where a downtown street actually is a divider, this can be shown too, but there is no way to find this out except by walking and looking.

The customer is right

In this dependence on maps as some sort of higher reality, project planners and urban designers assume they can create a promenade simply by mapping one in where they want it, then having it built. But a promenade needs promenaders. People have very concrete reasons for where they walk downtown, and whoever would beguile them had better provide those reasons.

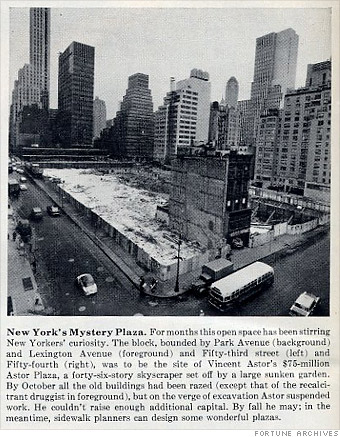

The handsome, glittering stretch of newly rebuilt Park Avenue in New York is an illustration of this stubborn point. People simply do not walk there in the crowds they should to justify this elegant asset to the city with its extraordinary crown jewels, Lever House and the new bronze Seagram Building. The office workers and visitors who pour from these buildings turn off, far more often than not, to Lexington Avenue on the east or Madison Avenue on the west. Assuming that the customer is right, an assumption that must be made about the users of downtown, it is obvious that Lexington and Madison have something that Park doesn’t.

The already cleared site for the postponed Astor Plaza building offers a great opportunity to provide the missing come-on and make Park Avenue a genuine promenade for many blocks. Instead of being aloof and formal, the ground level of this site ought to have the most commercially astute and urbane collection possible of one- and two-story shops, terraced restaurants, bars, fountains, and nooks. The Seagram tower and Lever House with their plazas, far from being disparaged, would then harvest their full value of glory and individuality; they would have a foil.

The deliberately planned promenade minus promenaders can be seen in the first of the “greenway” streets developed in Philadelphia. Here are the trees, broad sidewalks, and planned vistas–and there are no strollers. Parallel, just a few hundred feet away, is a messy street bordered with stores and activities–jammed with people. This paradox has not been lost on Philadelphia’s planners: along the next greenways they intend to include at least a few commercial establishments.

Fortunately, Philadelphia’s planners and civic leaders are great walkers, and one result is their unusually strong interest in trying to reinforce the natural attractions of the city’s streets. “We ought to do it a street at a time,” says Harry Batten, chairman of the board of N.W. Ayer & Son and a leading figure in the Greater Philadelphia Movement. “Take Chestnut, which is a fine shopping street; we ought to get rid of everything that hurts it, like parking-lot holes. Find merchants who ought to be there and sell them on the idea of relocating.” At the other end of the pole is

Market Street opposite Penn Center: cheap stores, magic shops, movie houses, and garish signs–exactly the kind of street most cities see as a blight. Batten, who thinks a city is made up of all kinds of people, is against making Market Street more prim. “It should be made more like a carnival,” he says, “more lights, more color.”

Focus

All the truly great downtown focal points carry a surprise that does not stale. No matter how many times you see Times Square, with its illuminated soda-pop waterfalls, animated facial tissues, and steaming neon coffee cups, alive with its crowds, it always makes your eves pop. No matter how many times you look along Boston’s Newbury Street, the steeple of the Arlington Street Church always comes as a delight to the eye.

Focal points are too often lacking where they would count most, at places where crowds and activities converge. Chicago, for instance, lacks any focal point within the Loop. In other cities perfectly placed points in the midst of great pedestrian traffic have too little made of them–Cleveland’s drab public square, for example, so full of possibilities, or the neglected old Diamond Market in Pittsburgh, which, with just a little showmanship, could be a fine threshold to Gateway Center.

Unfortunately, most of the focal points that are being planned seem foredoomed to failure. Those ponderous collections of government architecture, known as civic centers, are the prime example. San Francisco’s, built some twenty years ago, should have been a warning, but Detroit and New Orleans are now building centers similarly pretentious and dull, and many other cities are planning to do the same. Without exception, the new civic centers squander space; they spread out the concrete, lay miles of walk–indeed, planners want so much acreage for civic centers now that the thing to do is to move them out of downtown altogether, as New Orleans is doing. In other words, the people supposedly need so much space it must be moved away from the people.

But city halls never have needed much grounds, if any, a fact that our ancestors– who knew why they wanted courthouse squares—grasped very well. Newspapermen who make it their business to know politicians soon discover their own city has a kind of political Venturi–one spot where politicians gather, one stretch of sidewalk where, if you stand there at noon, you will see “everybody in town.” Even in the largest metropolitan centers you will find the political Venturi easy to spot; it is here that lawyers, officeholders, office seekers, various types of insiders and would-be insiders, cluster and thrive, for information is their staff of life. This vital trading post is never marked on the official city map; nor have the city’s architects found space or color for it in their diagrams of Tomorrow’s City. In fact, if you ask some of them about it, all you get is a blank look, perhaps a bit of scorn.

Big open spaces are not functional for this kind of civic activity; the prestige and attractiveness of a sidewalk garden, such as that of the new Federal Reserve Bank in Jacksonville, or a side garden, such as that of the Federal Reserve in Philadelphia, would be about right for city halls and city-county offices and would enable them to stay where they belong, near the lawyers, pressure groups, and others who must deal with the local government.

The echo

Backers of the project approach often argue that giant superblock projects are the only feasible means of rebuilding downtown. Projects, they point out, can get government redevelopment funds to help pay for land and the high cost of clearing it. Projects afford a means of getting open spaces in the city with no direct charge on the municipal budget for buying or maintaining them. Projects are preferred by big developers, as more profitable to put up than single buildings. Projects are liked by the lending departments of insurance companies, because a big loan requires less investigation and fewer decisions than a collection of small loans; the larger the project and the more separated from its environs, moreover, the less the lender thinks he need worry about contamination from the rest of the city. And projects can tap the public powers of eminent domain; they don’t have to be huge for this tool to be used, but they can be, and so they are.

Architects, similarly, lament that they have little influence over the appearance and arrangement of projects. They point out that redevelopment laws, administrative rulings, and economics resulting from the laws do their designing for them. This is particularly true in residential projects, where stipulations about densities, ground coverage, rent ranges, and the like in effect not only dictate the number, size and placement of buildings, but greatly influence the design of them as well (including such items as doorways and balconies). Nonresidential projects are less regulated, but they are cast in much the same mold, and many an office-building project is all but indistinguishable from an apartment-building project.

The developers and architects have a point. They have a point because government officials, planners–and developers and architects—first envisioned the spectacular project, and little else, as the solution to rebuilding the city. Redevelopment legislation and the economics resulting from it were born of this thinking and tailored for prototype project designs much like those being constructed today. The image was built into the machinery; now the machinery reproduces the image.

Where is this place?

The project approach thus adds nothing to the individuality of a city; quite the opposite–most of the projects reflect a positive mania for obliterating a city’s individuality. They obliterate it even when great gifts of nature are involved. For example, Cleveland, wishing to do something impressive on the shore of Lake Erie, is planning to build an isolated convention center, and the whole thing is to be put on and under a vast, level concrete platform. You will never know you are on a lake shore, except for the distant view of water.

But every downtown can capitalize on its own peculiar combinations of past and present, climate and topography, or accidents of growth. Pittsburgh is on the right track at Mellon Square (an ideally located focal point), where the sidewalk gives way to tall stairways, animated by a cascade. This is a fine dramatization of Pittsburgh’s hilliness, and it is used naturally where the street slopes steeply.

Waterfronts are a great asset, but few cities are doing anything with them. Of the dozens of our cities that have river fronts downtown, only one, San Antonio, has made of this feature a unique amenity. Go to New Orleans and you find that the only way to discover the Mississippi is through an uninviting, enclosed runway leading to a ferry. The view is worth the trip, yet there is not a restaurant on the river frontage, nor tiny roof top restaurants from which to view the steamers, no place from which to see the bananas unloaded or watch the drilling rigs and dredges operating. New Orleans found a character in the charming past of the Vieux Carre, but the character of the past is not enough for any city, even New Orleans.

A sense of place is built up, in the end, from many little things too, some so small people take them for granted, and yet the lack of them takes the flavor out of the city: irregularities in level, so often bulldozed away; different kinds of paving, signs and fireplugs and street lights, white marble stoops.

The two-shift city

It should be unnecessary to observe that the parts of downtown we have been discussing make up a whole. Unfortunately, it is necessary; the project approach that now dominates most thinking assumes that it is desirable to single out activities and redistribute them in an orderly fashion–a civic center here, a cultural center there.

But this nation of order is irreconcilably opposed to the way in which a downtown actually works; what makes it lively is the way so many different kinds of activity tend to support each other. We are accustomed to thinking of downtowns as divided into functional districts–financial, shopping, theatre–and so they are, but only to a degree. As soon as an area gets too exclusively devoted to one type of activity and its direct convenience services, it gets into trouble; it loses its appeal to the users of downtown and it is in danger of becoming a has-been. In New York the area with the mast luxuriant mixture of basic activities, midtown, has demonstrated an overwhelmingly greater attractive power for new building than lower Manhattan, even for managerial headquarters, which, in lower Manhattan, would be close to all the big financial houses and law firms–and far away from almost everything else.

Where you find the liveliest downtown you will find one with the basic activities to support two shifts of foot traffic. By night it is just as busy as it is by day. New York’s Fifty-seventh Street is a good example: it works by night because of the apartments and residential hotels nearby; because of Carnegie Hall; because of the music, dance, and drama studios and special motion-picture theatres that have been generated by Carnegie Hall. It works by day because of small office buildings on the street and very large office buildings to the east and west. A two-shift operation like this is very stimulating to restaurants, because they get both lunch and dinner trade. But it also encourages every kind of shop or service that is specialized, and needs a clientele sifted from all sorts of population.

It is folly for a downtown to frustrate two-shift operation, as Pittsburgh, for one, is about to do. Pittsburgh is a one-shift downtown but theoretically this could be partly remedied by its new civic auditorium project, to which, later, a symphony hall and apartments are to be added. The site immediately adjoins Pittsburgh’s downtown, and the new facilities could have been tied into the older downtown streets. Open space of urban—not suburban–dimensions could have created a focal point or pleasure grounds, a close, magnetic juncture between the old and the new, not a barrier. However, Pittsburgh’s plans miss the whole point. Every conceivable device–arterial highways, a wide belt of park, parking lots—separates the new project from downtown. The only thing missing is an unscalable wall.

[infobox]Downtown has had the capability of providing something for everybody only because it has been created by everybody.[/infobox]The project will make an impressive sight from the downtown office towers, but for all it can do to revitalize downtown it might as well be miles away. The mistake has been made before, and the results are predictable ; for example, the St. Louis auditorium and opera house, isolated by grounds and institutional buildings from downtown, has generated no surrounding activity in its twenty-four years of existence!

Wanted: careful seeding

When it comes to locating cultural activities, planners could learn a lesson from the New York Public Library; it chooses locations as any good merchant would. It is no accident that its main building sits on one of the best corners in New York, Forty-second Street and Fifth Avenue, a noble focal point. Back in 1895, the newly formed library committee debated what sort of institution it should form. Deciding to serve as many people as possible, it chose what looked like the central spot in the northward-growing city, asked for and got it.

Today the library locates branches by tentatively picking a spot where foot traffic is heavy. It tries out the spot with a parked bookmobile, and if results are up to expectations it may rent a store for a temporary trial library. Only after it is sure it has the right place to reach the most customers does it build. Recently the library has put up a fine new main circulation branch right off Fifth Avenue on Fifty-third Street, in the heart of the most active office-building area, and increased its daily circulations by 5,000 at one crack.

The point, to repeat, is to work with the city. Bedraggled and abused as they are, our downtowns do work. They need help, not wholesale razing. Boston is an example of a downtown with excellent fundamentals of compactness, variety, contrast, surprise, character, good open spaces, and a mixture of basic activities. When Boston’s leaders get going on urban renewal, Philadelphia and Pittsburgh can show them how to organize, Fort Worth can suggest how to handle traffic, and Boston will have one of the finest downtowns extant.

The citizen

The remarkable intricacy and liveliness of downtown can never be created by the abstract logic of a few men. Downtown has had the capability of providing something for everybody only because it has been created by everybody. So it should be in the future; planners and architects have a vital contribution to make, but the citizen has a more vital one. It is his city, after all; his job is not merely to sell plans made by others, it is to get into the thick of the planning job himself.

He does not have to be a planner or an architect, or arrogate their functions, to ask the right questions:

— How can new buildings or projects capitalize on the city’s unique qualities? Does the city have a waterfront that could be exploited? An unusual topography?

— How can the city tie in its old buildings with its new ones, so that each complements the other and reinforces the quality of continuity the city should have?

— Can the new projects be tied into downtown streets? The best available sites may be outside downtown–but how far outside of downtown? Does the choice of site anticipate normal growth, or is the site so far away that it will gain no support from downtown, and give it none?

— Does new building exploit the strong qualities of the street—or virtually obliterate the street?

— Will the new project mix all kinds of activities together, or does it mistakenly segregate them?

In short, will the city be any fun? The citizen can be the ultimate expert on this; what is needed is an observant eye, curiosity about people, and a willingness to walk. He should walk not only the streets of his own city, but those of every city he visits.

When he has the chance, he should insist on an hour’s walk in the loveliest park, the finest public square in town, and where there is a handy bench he should sit and watch the people for a while. He will understand his own city the better–and, perhaps, steal a few ideas.

[infobox]Designing a dream city is easy; rebuilding a living one takes imagination.[/infobox]Let the citizens decide what end results they want, and they can adapt the rebuilding machinery to suit them. If new laws are needed, they can agitate to get them. The citizens of Fort Worth, for example, are doing this now; indeed, citizens in every big city planning hefty redevelopment have had to push for special legislation.

What a wonderful challenge there is! Rarely before has the citizen had such a chance to reshape the city, and to make it the kind of city that he likes and that others will too. If this means leaving room for the incongruous, or the vulgar or the strange, that is part of the challenge, not the problem.

Designing a dream city is easy; rebuilding a living one takes imagination.