“Traffic is down 12 percent in Gothenburg, and transit use is on the rise.”

When you think of congestion pricing—the road charges often seen as the best hope for reducing traffic—big cities come to mind. Existing programs in Singapore, London, Stockholm, and Milan, for instance, or the ongoing push to create a pricing zone in New York. But despite its smaller size and modest transit coverage, Gothenburg, Sweden, introduced a congestion zone in January 2013, and the early returns suggest it’s been a big success.

So conclude Sweden-based researchers Maria Börjesson and Ida Kristoffersson in a new analysis of the Gothenburg program. They find that the congestion zone was effective in reducing traffic—down some 12 percent during the charging hours—with many commuters switching to public transportation. That such trends emerged in Gothenburg suggest the basic effectiveness of road pricing holds true across metros of varying density and transit coverage; here’s Börjesson and Kristoffersson:

“We find that many effects and adaptation strategies are similar to those found in Stockholm, indicating a high transferability between smaller and larger cities with substantial differences in public transport use.”

Gothenburg isn’t exactly a small city; with half a million people, it’s the second largest in Sweden. But its traffic congestion isn’t on par with that of a Stockholm, and its transit commute share in areas where congestion charges would later emerge was just 26 percent in 2012, according to Börjesson and Kristoffersson. (By comparison, that figure in Stockholm is closer to 77 percent.) Relative to Stockholm, Gothenburg also has a lower population density and wider job distribution, factors typically conducive to driving.

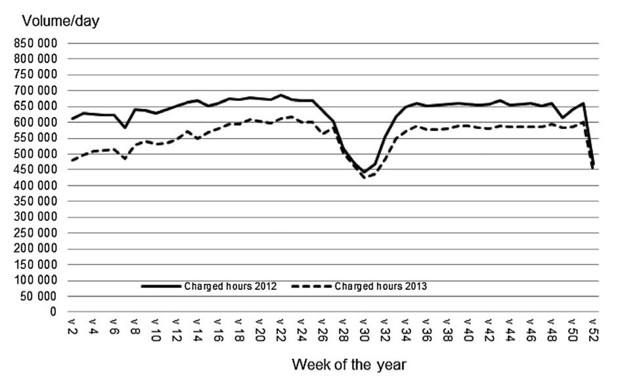

And yet after Gothenburg introduced a congestion charge that varied by time in 2013, it experienced many of the same benefits seen in bigger city pricing programs. Traffic declined about 12 percent during the charged hours (6 a.m. to 6:30 p.m. on weekdays):

From our partners:

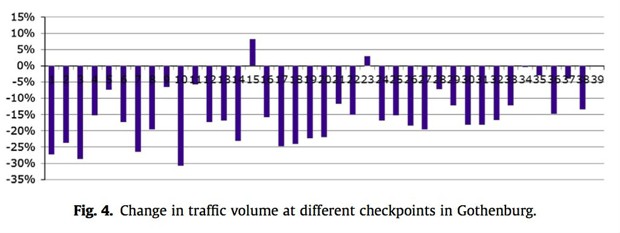

Reductions occurred at all but two of the charging checkpoints:

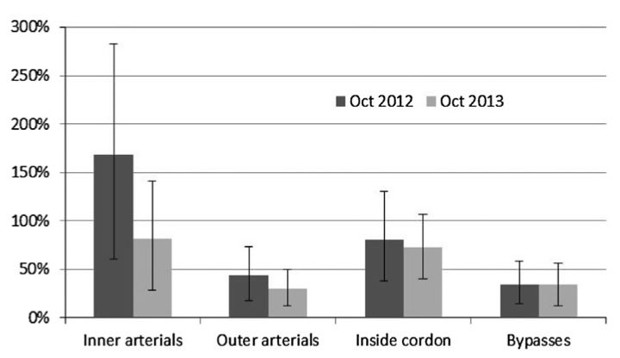

Morning commute travel times declined—especially on inner arterials—relative to pre-congestion levels:

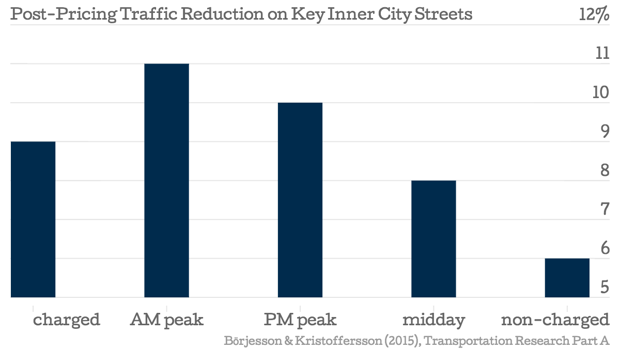

Traffic on 10 key inner-city streets fell 9 percent during the charging hours, on average, and 11 percent during the morning rush:

And, at least according to one survey of 3,000 locals, car commuting declined about 9 percent while public transit use by commuters spiked 24 percent (though all travel declined for non-work trips):

Not everything went according to plan. Initial projections actually called for a traffic reduction of 18 percent during the morning peak (it actually fell 13 percent). And while commuters took more public transportation—no doubt because the city improved commuter rail and bus operations, adding frequency and bus lanes—non-work trips on transit declined. This may indicate that some people cut back on discretionary trips, while others might have chosen new destinations outside the charging zone.

The charges also grossed €72 million in the first year, according to Börjesson and Kristoffersson. That total was lower than initial projections (€93 million), but it was nearly on par with what Stockholm generated in 2013 (€76 million), despite Gothenburg’s considerably smaller population.

Perhaps the biggest takeaway from the Gothenburg analysis is that public support isn’t necessary to get a congestion pricing program going. In this case, at least, political will proved far more important. In a non-binding September 2014 referendum, 57 percent of metro Gothenburg residents preferred not to extend the program (with opponents primarily located outside the city). Officials chose to continue it anyway, largely because it’s the basis for a major regional infrastructure package.

But it should be noted that public enthusiasm for congestion charging in Gothenburg (as in Stockholm) has gone up as people become more familiar with it. Within the city, for instance, support was just above 30 percent in spring 2013. By fall 2014, it hovered closer to 55 percent—a clear majority.

This feature is adopted from CityLab