Greenland’s hunters are facing a threat to centuries of tradition.

Albert Lukassen’s world is melting around him. When the 64-year-old Inuit man was young, he could hunt by dogsled on the frozen Uummannaq Fjord, on Greenland’s west coast, until June. The photo above shows him there in April. All the photographs for this story were taken on the fjord.

LATE ONE QUIET NOVEMBER NIGHT in the village of Niaqornat, 300 miles above the Arctic Circle on Greenland’s west coast, the sled dogs began to howl. No one knew for sure, but some of the villagers suspected the dogs had heard the exhalations of narwhals. The whales with the spiral unicorn tusks usually swim into Uummannaq Fjord this time of year as they migrate south. The next morning most of the community’s men set out in small boats to try to bag a narwhal, as the Inuit in Greenland have done for centuries—though in this area nowadays they throw harpoons from motorboats moving at 30 knots and finish off their quarry with high-powered rifles.

That afternoon, beneath a lowering gray sky, the hunters return, dragging their boats ashore. A few more of Niaqornat’s 50 residents emerge from brightly painted wooden houses and gather on the stony beach, eager to see what the boats might hold. Among them is Ilannguaq Egede, the 41-year-old manager of the village power plant. He came here nine years ago from south Greenland, where sheep farmers far outnumber whalers, to be with a Niaqornat woman he met on an Internet dating site. “I haven’t caught my first narwhal yet,” he says. “I’m waiting for this season.”

From our partners:

“Now a culture that has evolved here over many centuries, adapting to the seasonal advance and retreat of sea ice, is facing the prospect that the ice will retreat for good.”

Maybe the narwhals eluded their pursuers. Or maybe they were never there and are still lingering in their summer grounds up north, not yet driven south by spreading sea ice. Whatever the reason, Niaqornat’s hunters have returned with smaller prey: ringed seals, a dietary staple. Within minutes the animals have been skinned, the meat cut and carried away in plastic bags. Bite-size slices of raw liver have been handed to delighted children. Aside from some bloodstained rocks and a few severed flippers, all traces of the seals have vanished.

Something else is vanishing here too: a way of life. Young people are fleeing small hunting villages like Niaqornat. Some of the villages struggle to support themselves. And now a culture that has evolved here over many centuries, adapting to the seasonal advance and retreat of sea ice, is facing the prospect that the ice will retreat for good. Can such a culture survive? What will be lost if it can’t?

On the beach Egede demonstrates what a narwhal sounds like when surfacing for air. “You can hear them breathing,” he says. He takes a deep breath, holds it, and then exhales with an explosive whoosh. “Like that.”

WHEN THE SEA FREEZES, the world of the north suddenly becomes larger. Horizons expand even as daylight contracts. Greenlanders, all 56,000 of them, live their lives facing seaward, with a vast, uninhabitable interior at their backs. No roads cross the glaciers and plunging fjords that separate the scattered coastal towns. These days planes, helicopters, and fast motorboats help connect them—but traditionally, at least in more northerly places like Uummannaq, it was sea ice that brought an end to isolation and autumnal little-town blues. In winter dogsleds, snowmobiles, even taxis and fuel trucks can maneuver across what had been open water. For as long as the Inuit have been in Greenland, winter has been the time for visits, journeys, and hunts.

Of the 2,200 people who live along Uummannaq Fjord, more than half are on its namesake island, on the slopes of a 3,840-foot-high peak called Heart-Shaped (Uummannaq in Greenlandic) Mountain. The town has steep, narrow roads with cars on them; it has stores, a hospital, and bars. It’s the region’s commercial and social hub, the place where people in the seven outlying settlements, including Niaqornat, send their children to high school and come to shop. In Uummannaq you can work as an auto mechanic, social worker, or teacher.

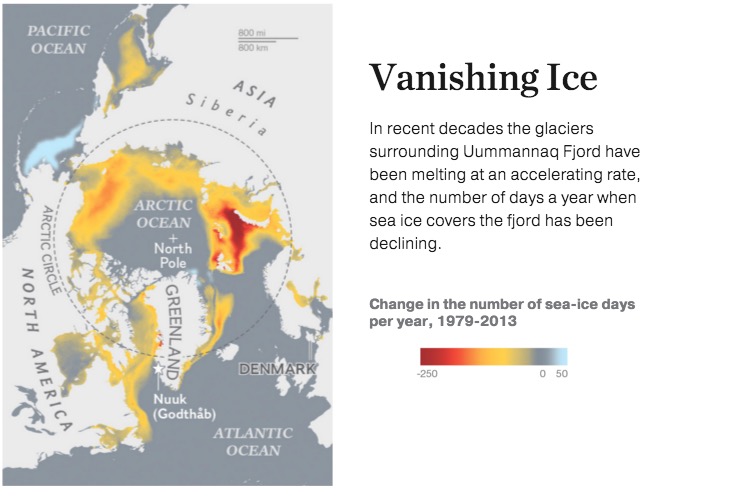

SOURCE: CLAIRE L. PARKINSON, NASA GODDARD SPACE FLIGHT CENTER

In the settlements, people make a living by hunting and fishing. Whale and seal meat are an important part of the diet, but their export is largely banned. The real moneymaker is halibut.

Many settlements have a fish factory operated by Royal Greenland, a government-owned company that processes and packages the halibut for export. Halibut fishing is a year-round occupation. When there’s no ice, fishermen set out long lines in the fjord with hundreds of baited hooks. In the winter they cut knee-deep holes in the sea ice, sink their lines, which are hundreds of feet long, and reel in their catch with a winch. On a good day, a fisherman might load his boat or dogsled with a quarter ton or more of the flat, dull-brown fish and sell them to Royal Greenland for several hundred dollars.

Although fishing provides a good income for many families, the smallest settlements wouldn’t survive without generous government subsidies. Even the most remote communities have heliports, cell towers, grocery stores, clinics, and elementary schools—all subsidized by an annual block grant from Denmark, which stands at $580 million and accounts for a quarter of Greenland’s gross domestic product. Greenlanders who dream of full independence from their former colonial master—right now Greenland is in charge only of its domestic policy—pin their hopes on mineral wealth and offshore oil. But the oil fields haven’t been developed yet, and according to one recent study, mining would require so many immigrant workers that Greenlanders might become a minority in their own land.

CLIMATE CHANGE IS MAKING the economies of the settlements even more precarious. It has lengthened the periods in winter and spring when ice is too thick for boats to leave harbors yet not thick enough to support sleds or snowmobiles. The unsafe ice affects fishing, but it hurts the region’s hunters more.

“In the 1980s we had cold winters,” says Uunartoq Løvstrøm, a lean 72-year-old hunter and one of 200 residents of Saattut, a small island near the head of Uummannaq Fjord. “And ice was this thick,” he says, rising from a sofa and placing his hand even with his hip. We’re in the living room of his blue wood-frame home, a short, slippery walk from Saattut’s harbor. On the low table between us are some polar bear claws, souvenirs from a long-ago hunt. A large flat-screen television is temporarily muted. Sled dogs nap outside in the early gloaming.

At the height of winter in recent years, says Løvstrøm, ice in the fjord might be only a foot thick. Instead of icing over in December or January and melting in June, the sea freezes in February and starts to thaw in April. The loss of ice has shortened the hunting season, in a land where wild meat helps families get by: Seal, reindeer, and whale meat fills freezers for the year. And shooting seals from boats is a poor substitute for the traditional dogsled hunt. A hunter on a sled can get off and stealthily approach his prey. On a noisy boat, he can’t get as close; from a distance he must take a difficult shot at a seal coming up for air in open water.

When a hunter does bag a seal, it sinks through a surface layer of fresh glacial meltwater and floats on top of the salt water below. The hunter has to haul it up. But the glaciers flowing into Uummannaq Fjord are melting faster than ever. The freshwater layer is getting thicker, so the dead seals sink deeper. Sometimes now they’re out of reach.

PEAK ICE SEASON IS STILL AT LEAST three months away on the crystalline October day when I join Løvstrøm’s 66-year-old brother, Thomas, as he heads out to feed his sled dogs, of which he has too many to keep in the small yard around his home. We board his 14-foot-long open boat, and after we clear the growlers—small icebergs—in Saattut’s harbor, he guns the outboard motor.

To the east we can just make out a wall of white—the 200-foot-high face of a glacier flowing out from the inland ice sheet, which Løvstrøm says has retreated more than half a mile in the past decade. To the north and south, umber cliffs dusted with snow tower above the sapphire waters of the fjord. Soon we pull into one of the innumerable inlets. Keenly watching us from a bare outcrop are Løvstrøm’s dogs.

Greenland’s dogs are one of the world’s oldest breeds, descended from animals that traveled with the Inuit when they began their journey from Siberia to Greenland a millennium ago. Almost all are kept chained as adults; they’re free to roam only as puppies. They’re working dogs, not pets, fierce enough to confront a polar bear and bred to find contentment harnessed to a sled pulling heavy loads over ice. They’re also one of the lesser known casualties of climate change. Because of the shorter ice season, some hunters can no longer afford to keep their dogs year-round—especially given the easy availability of snowmobiles, which don’t need to be fed in the off-season. Some hunters have been pushed to an extreme: They’ve been killing their dogs.

Neither of the Løvstrøm brothers has reached that point, and for this season they have more than enough meat for their dogs. A few days ago hunters from Saattut killed some 40 pilot whales in a single day—a windfall that will fill the settlement’s larders for months. Thomas has brought some of the meat for his dogs. Chunks of whale carcass as big as tree stumps and frozen as hard and smooth as lacquered wood sit on the rocks, beyond reach of canine jaws. Thomas, walking nimbly over the slick terrain, saws off stiff planks of black skin and white blubber and tosses them to the dogs, which yelp and strain against their chains.

Later that afternoon at his house, in a living room where family photos share space on the walls with old whalebone tools, Thomas talks about how Greenland has changed since his youth. “Until 1965 my family only had rowboats, no motors,” he says. “My father was a great hunter. He still hunted narwhals from a kayak when he was 75 years old. Everything he needed for hunting—kayaks, tools, harpoons—he made himself.”

“Glancing at his grandchildren sprawled on the floor, transfixed by small screens, he says, “They’re more interested in iPads and computers.”

THE OLD WAYS HOLD LITTLE APPEAL for Malik Løvstrøm (no relation to the Løvstrøm brothers), a slender, 24-year-old drummer with a local band who has lived in Uummannaq all his life. His tastes run to hard rock and horror films, not seal hunting or halibut fishing. He taught himself English by listening to music, and he dreams of working as a tour guide on the cruise ships that ply Greenland’s fjords in the summer. He knows he ought to move to a larger town like Ilulissat or Nuuk, but that would leave no one to care for his 80-year-old grandmother, his aanaa, who raised him. So he remains in Uummannaq.

On a blustery day punctuated by snow flurries, Malik, dressed in his habitual black and plugged into his tablet, takes me to his favorite spot: a high rocky hill with sweeping views of the fjord and its monumental icebergs, not yet immobilized by sea ice. Rising above us at the north end of the island is Heart-Shaped Mountain. “This is where you can listen to music and think,” he says, looking across the fjord through heavy black-frame glasses. “I spend a lot of time here with my friends relaxing, watching the sun rise. In a few weeks we won’t have sun here again until February 4.”

He points to a name scratched on a graffiti-covered wall. “That’s my best friend, who died f

Greenland has one of the highest suicide rates in the world, with men in their late teens and early 20s accounting for most of the deaths. Researchers have proposed any number of causes: modernization (suicide numbers started to climb in the 1950s), sleep patterns disrupted by round-the-clock summer light, isolation, alcoholism. No single explanation adequately explains the ongoing national tragedy. But it is clearly emblematic of the uncertain future that awaits so many of Greenland’s youths, in particular those living in far-flung settlements like the ones on Uummannaq Fjord.

Climate change is only aggravating the settlements’ fundamental problem. The traditional hunting and fishing economy can’t pay for access to the modern amenities that have become important to the hunters and fishers themselves, let alone to their children. Long before the sea ice disappears, such economic and social pressure might force the abandonment of the settlements. The question of what to do about them is a deeply contentious one in Greenland—as I come to appreciate one evening in Uummannaq, when I attend a kaffemik.

A kaffemik, one of which seems to be happening somewhere in Uummannaq almost every day, is a kind of community coffee party. Besides the usual coffee and pastries, this one features plates of whale meat—deliciously fatty both cooked and raw—fish, meats, soups, and drinks. After everyone has finished eating, a band plays Greenlandic folk music, accompanying their singing with piano, guitar, ice shaken in a glass, and a qilaat—a large, flat caribou-skin drum. They jam until two or three in the morning.

During a break in the music, Jean-Michel Huctin, a French anthropologist who has been studying the Uummannaq and other Inuit settlements for 18 years, gets into a lively discussion with a man from Nuuk, Greenland’s capital and largest town, with more than 16,000 people. The subject is the future of places like Niaqornat and Saattut—and whether they even have one. The Nuuk man, who prefers not to be quoted by name, is ambivalent about propping up the settlements with subsidies.

[infobox]“If we don’t move out of isolation, we will always be conservative,” he tells Huctin. “I don’t want to live in a museum. I don’t want to live in the old way. My son, my daughter should be part of the world.” By subsidizing the settlements, he thinks, the government is providing “welfare for hunters” and slotting young people into a life of hunting and fishing rather than encouraging them to look beyond tradition.

[/infobox]“The Inuit hunters have Ph.D.’s in living in nature. I think these small, remote communities can invent a sustainable future for themselves.”

But job opportunities in Greenland are few, Huctin retorts, and anyway what would happen to older hunters such as the Løvstrøm brothers? Should they trade their independence, give up their dogsleds, boats, and rifles for life in one of Nuuk’s grim apartment blocks? The loss of the settlements, Huctin says, would be a loss for all. They’re bastions of Inuit hunting culture. Somehow they should be maintained.

YET SETTLEMENTS ALL OVER GREENLAND are losing population. Niaqornat’s has fallen to 50, from 75 a decade ago. It came very close to being abandoned a few years back when the community’s fish-processing plant shut down. Niaqornat’s fishermen had to motor 40 miles to Uummannaq to sell their catch. It wasn’t a tenable situation. But rather than abandon their homes, Niaqornat’s residents pooled their savings and bought the processing plant. For now their community is hanging on.

And to one person at least, it has offered a new beginning. When Ilannguaq Egede became a lonely exception to Greenland’s demographic trends nine years ago, moving to Niaqornat to be with the love of his life, he was willing to take any job available. For several years he emptied the town’s bucket toilets. He’d call on each house daily and cart the waste to a beach, where he dumped it into the fjord. Eventually he moved on to managing the town’s power plant. Along the way he found something he didn’t know he’d lost: a life attuned to larger rhythms, to the passage of narwhals in the night or the wandering of reindeer in summer’s perpetual light. Now even Uummannaq, with its population of 1,248, seems almost unbearably overcrowded to him.

“I like it here a lot,” he says, as we walk from his office to Niaqornat’s beach. “I have a home and a nice salary. I don’t want to move anyplace else. And my girlfriend is here. She doesn’t want to move. You can feel the freshness here, and it’s open. In Uummannaq she feels closed in. There’s not enough air.”

After falling in love with northern Greenland on his first trip, photographer Ciril Jazbec spent nearly six months in the frozen land for this assignment. There he found a new favorite food—narwhal meat.

This feature originally appeared in National Geographic.