But it’s not the highly coveted numbers cities need. How helpful is the company’s new data tool?

Uber has long had a somewhat rocky relationship with cities, from its most recent public spat with San Francisco authorities over testing autonomous vehicles to its feud with New York City planners over access to the company’s ridership data. But in what seems like a move calculated to mend ties, Uber has opened up that cherished trove of info to city planners, researchers, and (eventually) the public.

Just a peek, though.

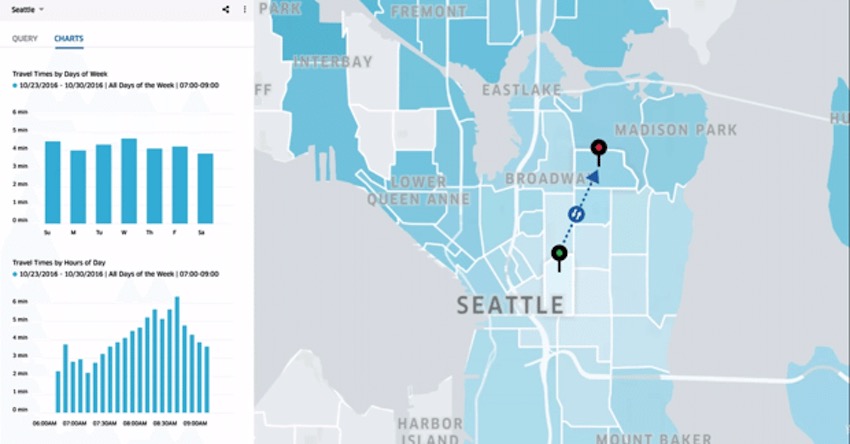

Uber isn’t releasing all the data collected over the last six years the company has been in operation. But its new tool, Movement, lets cities in on traffic patterns based on millions of trips taken over time. (The data released is anonymous.) The tool, which is currently available in Boston, Manila, Sydney, and Washington, D.C., tracks how long it takes to get from one point to another, and how that changes depending on the time of the day, day of the week, and factors like road shutdowns or city-wide events. It also allows users to look at patterns over a period of time.

That’s only one of the many ways Andrew Salzberg, Uber’s head of transportation, imagines cities can take advantage of the tool. It’s all part of the company’s efforts to improve its relationship with cities: In fact, Salzberg says that creating the product involved collaborating with city planners to figure out what they need.

From our partners:

At a recent launch event in D.C., Uber product manager Jordan Gilbertson showed off what Movement could do by showing what gridlock looked like when D.C. shut down its entire metro system in March for emergency inspections. (Non-scientific answer: hellish!) He plugged in the specific date and time, and the program did the rest. Analysis showed that overall, travel time in the city increased by anywhere from 10 to 30 percent. Along entry points to major highways, it was as much as 50 percent.

“It’s an act of contrition, in a way, allowing some of that data to be released.”

That experience served as a reminder that ride-hailing services, despite what they sometimes seem to say, are no replacement for true mass transit. “There’s no way in any system that Uber and any sharing models can move as many people as rail trains can, and I think we’ve demonstrated that with the shutdown,” Salzberg told reporters afterward. “If you look at the data for that day, you get a dramatic increase in congestion when rail transit doesn’t run. That’s one reason we’re putting this data out there—to be helpful in policy arguments around how to use these [road] spaces effectively.”

It isn’t quite the highly coveted data that cities want from Uber and the like. New York City, along with other local governments, is more interested in knowing when and where passengers get picked and dropped off—what Mayor Bill de Blasio has demanded and Uber has refused to deliver, on grounds of privacy protection for its riders.

So if city governments aren’t getting what they want from this tool, can Movement still be useful for local planners? Yes and no.

“A lot of cities, especially New York City, are fighting to get a lot more data from Uber, and it’s kind of an act of contrition, in a way, allowing some of that data to be released,” says Tim Welch, an assistant professor of city and regional planning at Georgia Tech. “It can be useful, but the level of detail and the type of data isn’t something that’s not already used by planners through other data sources.” Uber’s set of data is aggregated through Traffic Analysis Zones, which Welch says is a common unit of geography and planning analysis already used by cities. So in terms of how much further Movement contributes to urban planners’ work, he doesn’t think “it moves it much.”

But Zak Accuardi at the Transit Center, a New York-based foundation, says that while the data might not be nuanced enough for cities, regional transportation planners could benefit from that additional layer of traffic information when determining how road projects or new public transportation initiatives might impact travel time from one part of the region to another. He calls it a positive first step for both the company and cities to foster a relationship around data-sharing. “It opens the door for productive conversation for cities and makes it possible for cities to approach Uber and say, ‘We know you have this platform, and here’s what we’d like to see on it.’”

But it’s worth remembering that Uber is releasing this data on its own terms and may continue to keep certain information out of the public eye. Welch also notes that Uber’s data covers only a small subset of commuters: those who own smartphones and those who use Uber. “Planners ought to be very concerned about the lower-mobility groups,” he says. “How is the lower-income person in a location not using Uber getting around? And what kind of conditions are they facing?”

Uber’s Salzberg says this is just the beginning. And the company’s new commitment to swapping traffic intel with metros isn’t just about PR: In the end, Uber itself also stands to benefit from such civic collaboration (as do with other ride-sharing companies that collect their own data). “We ultimately benefit from streets that move effectively and from decisions made based on data,” he says. “We all share the goal of putting more people into fewer cars.”

This feature originally appeared in Citylab.