Citylab caught up with Yeampierre to discuss the National Day of Action and UPROSE’s efforts to help make sure Puerto Rico is rebuilt in a just fashion.

Puerto Rico will recover with new infrastructure and a refreshed built environment. Developers and green builders will say this is an opportunity to provide Puerto Rico with what it needed all along . How would you respond to that?

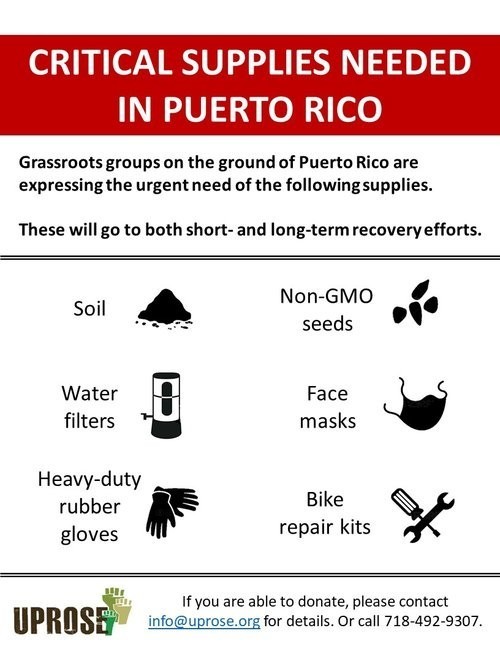

From our partners:

You once served as chair of NEJAC, the civilian committee that advises EPA on environmental justice issues, and that has produced several reports on not only how to do green rebuilding without gentrification, but also on how to do an environmental justice-guided recovery after natural disasters. What’s been your experience in terms of having EPA actually utilize these advisory reports?

One of the things that I had asked for [from EPA] before Sandy happened in New York was for a working group to put together a study on toxic exposure for industrial waterfront communities in the event of an extreme weather event. And that was a big fight. I had to keep asking [EPA] and then finally Sandy had to happen in order for us to get that working group going. And then we finally put out the report, but then the report just sat there. But now you see what happened in Houston, which is really the poster child for what that report was predicting could happen in our community.

So, one of the challenges is capacity on the ground. These grassroots organizations were always small to begin with and underfunded and under-supported. Now they’re taking on the huge challenge of trying to coordinate efforts throughout the island, from the frontlines to the grassroots. So this is really an opportunity to build their capacity so that they can drive what a just transition looks like. One of the issues we’re hearing is super important to them is food sovereignty. Before [Hurricane Maria] happened, 80 percent of the food came from outside of Puerto Rico. So this has basically knocked down what little agricultural land that was in the hands of the Puerto Rican people.

Talk about the role Puerto Rico, and Puerto Ricans such as yourself have played in developing the environmental justice movement from the beginning.

Well, you know, years ago in New York City my son was going to protests on a regular basis to stop the bombing in Vieques because it was creating an ecological disaster. There were people in Vieques who not only lost their homes but developed cancer. Now there are 23 Superfund sites in Puerto Rico that have swelled up and spilled all over the place because of the storm. When I was the NEJAC chair, I called a meeting with the heads of a bunch of [federal] agencies because they were planning a pipeline to traverse across the entire island. Puerto Ricans here have been fighting an ash plant on the island and there have been a number of Puerto Ricans in New York City leading that fight.

But Puerto Ricans here, you know, we came here because of U.S. policies on the island. A lot of us weren’t born here by choice. We came because the United States basically turned an agricultural economy into an economy for the petrochemical industry and other U.S.-based industries. And I know my grandfather could not find any work. Half of my grandmother’s children died from hunger and disease in Puerto Rico. And so that’s how we ended up here.

So whenever we can try to make a difference there we’re willing to do it. One thing that’s interesting is they could drop bombs on Vieques, but they can’t drop food on the island. I do think all the bureaucratic stuff is keeping people from accessing the resources. Folks in Miami and Connecticut and Boston and Chicago and New York City— you should see the looks on the people’s faces that are doing all this work, giving up all their weekends to send food because our people are in trauma right now. There are feelings that they’re trying to basically push us out of the island so that they can privatize it. Puerto Rico is literally at the mercy of a government who has over and over again let folks know that people of color are not their priority.

This feature first appeared in Citylab.